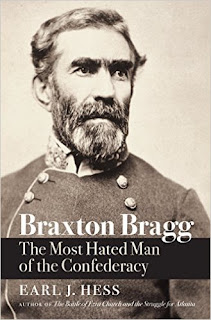

To put it mildly, the Civil War legacy of Confederate general Braxton Bragg has not been a positive one. His critics have charged him with all manner of serious offenses, including gross military incompetence, callous execution of his own men, and extreme levels of vindictiveness directed toward key subordinates. Then as now, however, there are those that have defended the North Carolinian, but their struggles against the tide have made little or no impact on the popular image of the general. Earl Hess's new book, Braxton Bragg: The Most Hated Man of the Confederacy, is less about elevating the historical stature of Bragg and more concerned with presenting a more dispassionately balanced picture of the general as both officer and man.

To put it mildly, the Civil War legacy of Confederate general Braxton Bragg has not been a positive one. His critics have charged him with all manner of serious offenses, including gross military incompetence, callous execution of his own men, and extreme levels of vindictiveness directed toward key subordinates. Then as now, however, there are those that have defended the North Carolinian, but their struggles against the tide have made little or no impact on the popular image of the general. Earl Hess's new book, Braxton Bragg: The Most Hated Man of the Confederacy, is less about elevating the historical stature of Bragg and more concerned with presenting a more dispassionately balanced picture of the general as both officer and man.The heart of the book is composed of Hess's chapter length analyses of Bragg's performance during those major western theater battles and campaigns of which he was a chief participant, first as a corps commander at Shiloh and later as a leader of armies at Perryville, Stones River, Chickamauga, and Chattanooga. Hess backs up his often strongly stated opinions with a judicious re-examination of the evidence. In the process, he directly and effectively highlights both points of departure and points of agreement with previous scholars.

No controversy exists regarding the quality of the troops Bragg brought to Shiloh from Pensacola. All observers agree that the corps Bragg led at Shiloh ranked among the best trained and organized bodies of Confederate troops. In examining the fighting at the famous Hornet's Nest sector of the battlefield, one aspect of the failed Confederate effort to carry the position by frontal assault that continues to puzzle is why Bragg singled out Randall Gibson's Louisiana brigade (and especially its leader) for such malignant calumny. By tracing the one-sided dispute's origin back to the general's low opinion of the Gibson family, Hess provides fresh pre-war context for an unfortunate wartime event that reflected poorly on Bragg's character. The unwarranted personal attack on Gibson also represented the first strong evidence of Bragg's general incapacity for managing subordinates in a manner that would inspire their loyalty.

In regard to the conception of the 1862 Kentucky Campaign, Hess joins others in praising Bragg's aggressive operational maneuver that seized the initiative in the West and completely turned the tables on the Union juggernaut. The book acknowledges those critics that believe Bragg would have been better off initiating battle early rather than later in the campaign, but persuasively cites the failure of ranking subordinate Leonidas Polk to follow Bragg's orders (either on time or at all) and the critical lack of cooperation from Edmund Kirby Smith as clear signals that no great result was likely to be accomplished by divided Confederate forces in the Bluegrass.

Hess sees Stones River as the apogee of Bragg's effectiveness as an army commander. The disastrous bungling that took place during the January 2, 1863 offensive is indefensible, but the author views the December 31, 1862 attack that crushed the Union right, and very nearly bent the might Army of the Cumberland back upon itself, as one of the war's best executed grand assaults. Hess frames the event in such a way that it is hard to disagree with him that the result of that day's fighting was at the very least a greatly underrated tactical accomplishment. However, in the aftermath of the battle, Bragg's decision to go on the offensive when it came to responding to critics would serve neither him nor the Confederacy well. Coming after similar results at Perryville, Stones River would also further solidify the pattern of half-victory that would plague Bragg's army command tenure.

Of course, Bragg's only undisputed battlefield success was at Chickamauga, and, even then, he would be assailed from all quarters (from brother officers, press, politicians, and the public) for not possessing the ability to turn a tactical victory into a strategic triumph. In the end, the rapid recovery of the Army of the Cumberland, combined with Union retention of Chattanooga itself, made Chickamauga appear more than more like a Union victory. Critics both inside and outside the army harped on Bragg's alleged do-nothing attitude after Chickamauga. Instead of crossing the river above or below the city and forcing the issue, Bragg's army settled into a siege, and a leaky one at that. Here again, Hess places readers in Bragg's shoes and asks them to consider the victorious Confederate army's very real problems and limitations. Aside from the devastating casualties suffered during the Chickamauga battle, half the army (representing nearly all the reinforcements Bragg received during the campaign) arrived on the field without transportation, and as much as a third of the artillery's horses were lost during the fighting. A strike across the Tennessee River would have been very risky under the best circumstances, and the chances for success decreased further when Bragg realized he had no corps commanders he could trust and his cavalry had theretofore proved similarly unreliable. A direct advance upon Chattanooga, and the adoption of a 'wait and see' stance, was the safest course to take and was Bragg's ultimate choice. Whether a desperate throw of the dice was warranted is a matter open to debate, but the best evidence seems to point toward such an operation being logistically impossible.

Essentially every scholar who was looked into the matter has come to the conclusion that Bragg's Army of Tennessee had the most dysfunctional command structure of any of the war's major field armies. Certainly, the opportunities fumbled by Bragg's chief subordinates (among others, Hindman/Buckner at McLemore's Cove and Polk/D.H. Hill at Chickamauga), often involving direct disobedience of orders, is a major theme in the book. But sins committed against command efficiency and harmony clearly flowed in both directions. Bragg seemed to have possessed a singularly perverse talent for courting the disdain of every corps commander appointed under him, and his vindictive behavior and general inability to conciliate disgruntled subordinates only made a bad situation worse. The general had an equally toxic relationship with the press. The incessant scheming of hostile subordinates and the constant stream of public ridicule coming from newspaper editors and reporters merged with Bragg's own failings to render his effective exercise of top command impossible. The general's apparently weak physical constitution did not help either, and Hess convincingly argues that the combination of factors mentioned above should have led to Bragg's resignation much earlier in his tenure. The subject of Bragg's ill health is only lightly addressed in the book's concluding chapter, which is a bit surprising given how often Bragg's "dyspepsia" is cited in the literature as one of the chief sources behind his abrasive personality.

On some level, the constant support of President Davis (due not to friendship, as is popularly believed, but on an honest appreciation of Bragg's military abilities) was laudable, but he too sustained Bragg at the head of the Army of Tennessee long after the general's leadership was fatally compromised. After the Chattanooga disaster finally led to Bragg's resignation, Davis still did not abandon him. While Bragg's appointment to the post of chief military advisor to the president was not greeted with enthusiasm by press or public, Hess does credit the general with administrative improvements and an important role in the 1864 campaigns in the East (most particularly the success at Bermuda Hundred). As the book shows, the new advisor's influence on Johnston and the war in the West was decidedly less fruitful, and Bragg's enthusiastic support of John Bell Hood's elevation to army command demonstrated questionable judgment.

Only on rare occasions in the book do Hess's assessments ring false. For one example, in regard to the suggestion that Richard Taylor take an important command within the Army of Tennessee, Hess dismisses Bragg's high regard for Taylor by writing that the Louisianan "had yet to distinguish himself in largely administrative commands held in the Trans-Mississippi." (pg. 236). In truth, as of July 1864, Taylor had already personally led numerous smaller scale military operations in SW Louisiana and triumphed leading a semi-independent corps-sized command against great odds during the Red River Campaign fought earlier in 1864. It would seem that the more important question regarding Taylor's suitability for replacing Hardee in Georgia would have revolved around the talented general's extensive history of vigorously disputatious insubordination, making him the kind of quarrelsome addition the Army of Tennessee's high command already had enough of at the time.

In the book, Hess develops a metric for assessing the relative success of Army of the Mississippi/Army of Tennessee commanding generals, one that involves adding up all the western army's days fighting battles and dividing them into "days of success" and "days of failure." With Bragg owning 75% of the western army's success days and only 28.5% of its failure days, the author concludes that Bragg's generalship compares quite favorably to that of his colleagues. One can certainly dispute the merits and relevance of such reductive calculations, but they do at some level reinforce the book's argument that Bragg was far from completely incompetent when it came to directing armies on the field of battle.

Throughout the book, Hess inserts excerpts from Bragg's correspondence with his wife, Elise. While dwelling so much on the general's marital relationship might seem strange for a military biography, it does serve the purpose of humanizing Bragg. As a man so often described as an imperious, unfeeling brute of a commander, the tenderness the letters display shows a side of Bragg that contrasts sharply with his popular image. Though Bragg indeed had legions of detractors within the army, Hess can point to evidence indicating that Bragg had warm admirers among division and brigade commanders. In letters home, common soldiers also wrote about how much they respected their commander, and the feeling was mutual. Bragg cared deeply for the welfare of his men. Army of Tennessee medical director Samuel Stout frequently testified to the general's sincere concern for the sick and wounded.

The popular belief, both inside and outside the army, that Bragg would have a soldier shot at the drop of a hat haunted the general throughout the war and for the rest of his life. However, the author could find no evidence that Bragg had soldiers summarily shot or that he approved death sentences at a rate exceeding that of other Civil War army commanders. In fact, Hess found the opposite to be true, with the much beloved Joe Johnston allowing a much higher percentage of capital sentences to be carried out than Bragg did. Though he doesn't have numbers to back it up, the author also suggests that Bragg was probably more lenient than Robert E. Lee, as well.

Braxton Bragg does not attempt to paint its subject as a great general. What it does do is very thoughtfully, and often persuasively, reconsider the positives and negatives of Bragg's character along with the successes and failures of his military career to come up with an assessment of his generalship and role in the war that is dramatically different from the traditional consensus view. Braxton Bragg, more than any other individual, has come to represent Confederate defeat in the West, and this important study successfully challenges the many stale caricatures of Bragg that remain deeply ingrained in the Civil War literature.

• Click here for more CWBA reviews of UNC Press titles •

A fine review of an excellent book.

ReplyDeleteI read it in galley and heartily recommended it in a published review and online.

The Richard Taylor issue somehow escaped me, but I thought Hess's old school handing of Hood the malcontent and bumbler was odd given the recent scholarship and information on that officer that has come to light. Given the large number of (generally outstanding) titles Hess has been putting out, it would not surprise me if he wrote much or all of this manuscript before the papers were discovered and made public.

All in all a wonderful addition to the literature that every Western Theater student should read and ponder.

Good to hear Hess gave Bragg a fair treatment. Such a biography needed to be written.

ReplyDeleteThanks for the excellent review.

ReplyDeleteBragg has always been one of my favorite characters from the war to study. He fascinates me. One of the great, dangerous, but not without some talent grouches of American military history.

Chris