PAGES:

▼

Tuesday, July 6, 2021

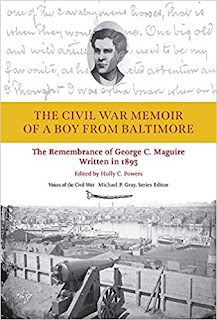

Review - "The Civil War Memoir of a Boy from Baltimore: The Remembrance of George C. Maguire, Written in 1893" by Holly Powers, ed.

[The Civil War Memoir of a Boy from Baltimore: The Remembrance of George C. Maguire, Written in 1893 edited by Holly I. Powers (University of Tennessee Press, 2021). Hardcover, photos, drawings, notes, bibliography, index. Pages:xxvi,133. ISBN:978-1-62190-335-2. $45]

A great multitude of underage soldiers served in the fighting ranks of Civil War armies of both sides (some estimates maintain that one-fifth of all Union soldiers were under the prescribed age of eighteen at enlistment). Impressed by the promise of grand adventure or any of a number of additional motivating factors, other boys too young to shoulder a rifle accompanied regiments as drummer boys or unit "mascots" looked after by the older officers and men. Mascots that demonstrated maturity beyond their years could even be assigned a certain degree of real responsibility in either official or unofficial roles. This was the case with Baltimore's George C. Maguire. Though his own deeds attained far less fame than those of some other Union child soldiers such as John Clem (a.k.a. "Johnny Shiloh"), Orion P. Howe, or Manny Root, young Maguire nevertheless contributed to the war in ways no less worthy of recognition. With the publication of The Civil War Memoir of a Boy from Baltimore: The Remembrance of George C. Maguire, Written in 1893, the newest volume in University of Tennessee Press's Voices of the Civil War series, a great many Civil War readers can now be fully exposed to Maguire's wartime activities through the efforts of editor Holly Powers.

In his memoir Maguire claimed to be "around 12" years of age when Fort Sumter was fired upon, but Powers's examination of census records indicates that he would have been closer to 14. The memoir's earliest wartime remembrances include observations of the violent 1861 rioting in Maguire's native Baltimore, made perhaps most interesting to today's readers for the writer's unconventional determination that the infamous assaults on passing Union soldiers were primarily motivated by false assumptions about the war and over two-thirds of the perpetrators would eventually see the error of their ways and enthusiastically join the Union Army. How Maguire arrived at such a number is unknown, but perhaps, as he came from a solidly pro-Union family, he wanted to present his fellow Baltimoreans in a more favorable (i.e. more loyal) light.

Maguire was allowed/invited to join his brother-in-law Lt. Salome Marsh (whom he lived with before the war) and two brothers in the Fifth Maryland, a volunteer infantry regiment that received its training at nearby Camp LaFayette and first field assignment at Fort Monroe in Virginia. The regiment did not participate in any of the Peninsula and Seven Days battles, and Maguire relates mostly boyish adventures on the Hampton Roads stretch of the Virginia Peninsula. However, during the 1862 Maryland Campaign Maguire would in more earnest begin his transformation from army tourist to active participant. He came under fire at Antietam (the Fifth was involved in the Second Corps attack on the Bloody Lane) and assisted the regimental surgeon in caring for the wounded. Traumatized by the experience, he returned home to Baltimore and reentered school. However, Maguire quickly became bored with the routine of home and school life, and rejoined the regiment at the end of 1862.

At the time of Maguire's return the Fifth was part of the Harpers Ferry garrison, and Lt. Marsh was provost marshal. Marsh employed the educated Maguire as an office clerk with document-issuing powers, and Maguire's memoir offers an eventful picture of Potomac River smuggling operations and the inner workings of the pass system for civilians traveling both directions through Harpers Ferry. This job would be his final one at the front. In June 1863, Maguire left the regiment altogether and returned home. There would be one final attempt to rejoin the war, though. Tempted by the considerable allure of the high fees being paid to late-war substitutes, Maguire tried to engage a broker in the city but was rejected.

In 1865, Maguire obtained employment at Maryland's new Thomas Hicks United States General Hospital. Impressed by his wartime experience (slim as it was) and his education, staff assigned Maguire a posting as Ward Master, and he was even given Medical Cadet status by the supervising physician as a way to allow Maguire to assume expanded duties related to direct patient care. Though this part of the memoir is relatively brief, it contains a number of empathetic patient stories as well as useful information regarding the layout and operation of the hospital. A number of Maguire's sketches are reproduced in the book, and the ones related to the hospital are the most revealing.

The memoir itself is a quick read, running sixty pages in the book. As part of her editorial duties, Powers contributes a scholarly introduction, a chapter-length conclusion, and extensive endnotes to the volume. Quite expansive discussions of persons, objects, places, and events are contained in her notes, and the editor frequently found in her research documented confirmation of Maguire's experiences and observations. Over the past few decades, the Civil War scholarship has examined in far more depth than ever before the many ways in which children engaged with the Civil War and were affected by it (most readers will be at least familiar with James Marten's work, but there are many others), and The Civil War Memoir of a Boy from Baltimore is another strong resource and contribution to that subfield.

No comments:

Post a Comment

***PLEASE READ BEFORE COMMENTING***: You must SIGN YOUR NAME ( First and Last) when submitting your comment. In order to maintain civil discourse and ease moderating duties, anonymous comments will be deleted. Comments containing outside promotions, self-promotion, and/or product links will also be removed. Thank you for your cooperation.