PAGES:

Tuesday, January 31, 2023

Booknotes: The Antietam Paintings by James Hope

• The Antietam Paintings by James Hope by Bradley M. Gottfried & Linda I. Gottfried (Author, 2022). Except for the too-perfect alignment of battle lines in some of them, I've always liked the Hope series of paintings depicting scenes from the Battle of Antietam. According to the introduction to Bradley and Linda Gottfried's The Antietam Paintings by James Hope, Hope's work was directly informed by the artist's prewar painting background (during which he developed a passion for landscapes), his personal experience of the battle (he was a captain in the Second Vermont), and his topographical engineer duties during the war. From the description: "The Battle of Antietam held a special place for Hope, and during the late 1880's into the 1890's, he created five large panoramic paintings of various aspects of the battle. Four of the five still exist today and are regularly displayed at the Antietam National Battlefield; the fifth was badly damaged in a flood, but a smaller version still exists." In addition to learning more about Hope himself, I am looking forward to perusing the volume's breakdown of key features displayed in his painting series. More from the description: The 48-page booklet "describes Hope's life and then reviews each of the five panoramic paintings in detail, beginning with a representation of the entire painting and then by dividing the painting into three sections and illustrating the major features of each in subsequent pages. A full-color panel is on the right side of each page and a description of the events/scenes, is on the left."

Friday, January 27, 2023

Coming Soon (February '23 Edition)

• Cherokee Civil Warrior: Chief John Ross and the Struggle for Tribal Sovereignty by Dale Weeks.

• John T. Wilder: Union General, Southern Industrialist by Steven Cox.

• I Thank the Lord I Am Not a Yankee: Selections from Fanny Andrews's Wartime and Postwar Journals by Stephen Davis.

• Decisions at Shiloh: The Twenty-Two Critical Decisions That Defined the Battle by David Powell.

• Of Age: Boy Soldiers and Military Power in the Civil War Era by Frances Clarke & Rebecca Jo Plant.

• Civil War Torpedoes and the Global Development of Landmine Warfare by Earl Hess.

• Lansing and the Civil War by Matthew VanAcker.

• Pulpits of the Lost Cause: The Faith and Politics of Former Confederate Chaplains during Reconstruction by Steve Longenecker.

• The Maps of Spotsylvania through Cold Harbor: An Atlas of the Fighting at Spotsylvania Court House Through Cold Harbor, Including all Cavalry Operations, May 7 through June 3, 1864 by Bradley Gottfried.

• The Confederate Jurist: The Legal Life of Judah P. Benjamin by William Gilmore.

Comments: Another pretty light month. Cherokee Civil Warrior and Of Age received early releases and are available now. The Decisions series books often go through multiple release dates before finally landing, so hopefully Dave Powell's Shiloh installment (previously slated for last July) will hit its current 2/10 street date. I'm looking forward to that one. I hope to get a review copy of this latest Hess book, too. It will be interesting to see what it has to add to what was good coverage of the same ground in Kenneth Rutherford's America’s Buried History: Landmines in the Civil War (2020).

1 - These monthly release lists are not meant to be exhaustive compilations of non-fiction releases. They do not include non-revised/expanded reprints of previously published books, special editions not distributed to reviewers, and digital-only titles. Works that only tangentially address the war years are also generally excluded. Inevitably, one or more titles on this list will get a rescheduled release (and they do not get repeated later), so revisiting the past few "Coming Soon" posts is the best way to pick up stragglers.

Wednesday, January 25, 2023

Booknotes: The 117th New York Infantry in the Civil War

• The 117th New York Infantry in the Civil War: A History and Roster by James S. Pula (McFarland, 2023). Organized in Oneida County, New York in response to Lincoln's urgent summer 1862 call for 300,000 more volunteers, the 117th New York Volunteer Infantry (nicknamed the "4th Oneida Regiment") was placed under the command of West Point-trained Col. William R. Pease. After training and some initial seasoning through Washington D.C. area garrison duty, the regiment was shipped off to SE Virginia. Attached to the Seventh Corps, the 117th NY was involved in the 1863 Suffolk siege as well as Dix's Peninsula campaign of that year. Subsequently transferred to the Tenth Corps in South Carolina, the regiment participated in Charleston siege operations on Folly and Morris islands until April of 1864. With the Overland Campaign in Virginia in full swing soon after, the 117th returned to front line duty in the eastern theater with the Army of the James, fighting in the Bermuda Hundred campaign and other battles on the Richmond-Petersburg front. Later, the unit participated in both major efforts at capturing Fort Fisher (unsuccessfully in December 1864 and successfully mere weeks later in January 1865), before marching through Wilmington and triumphantly entering Raleigh on April 13. The role played by the 117th NY in all of these events is recounted in James Pula's The 117th New York Infantry in the Civil War. In creating this study, the author relied on a wide range of primary and secondary sources, including extensive archival research in diaries and correspondence. The detailed narrative derived from that research is supported by a fine-looking set of campaign and battlefield maps. Among other items of interest, the appendix section that follows it contains an extensive unit roster that significantly adds to the book's value. Much like the Connecticut unit history I reviewed last week, this study follows a regiment with a less than conventional eastern theater service history. In a publishing category understandably crowded with regiments closely tied to the Army of the Potomac, it's always refreshing to come across something different.

Monday, January 23, 2023

Booknotes: The Tale Untwisted

• The Tale Untwisted: General George B. McClellan, the Maryland Campaign, and the Discovery of Lee’s Lost Orders by Gene M. Thorp & Alexander B. Rossino (Savas Beatie, 2023). The fortuitous discovery by Union troops of a copy of Robert E. Lee’s Special Orders No. 191 during the 1862 Maryland Campaign is widely regarded as the Civil War's greatest military intelligence coup. The standard story is that McClellan, upon receipt of the document, inexcusably delayed in acting upon it, and, when he finally did, he threw his newfound advantage away through an abundance of overcaution. In recent years, this ingrained narrative has been persuasively challenged in several ways. In addition to questioning the true value of the presumed information bonanza that fell into McClellan's lap, some recent writers have argued that McClellan actually wasted little time in assessing the situation, and they have credited his army's movements with much more celerity than books and articles have traditionally allowed. From the description: In The Tale Untwisted: General George B. McClellan, the Maryland Campaign, and the Discovery of Lee’s Lost Orders, co-authors Gene Thorp and Alexander Rossino "document in exhaustive fashion how “Little Mac” in fact moved with uncharacteristic energy to counter the Confederate threat and take advantage of Lee’s divided forces, seizing the initiative and striking a blow in the process that wrecked Lee’s plans and sent his army reeling back toward Virginia." Few would argue that McClellan's overall conduct in response to Lee's invasion of Maryland was a masterpiece of generalship, but I think the old standard narrative of Little Mac's gross mishandling of the Lost Orders has been rendered mostly untenable at this point (though it seems there are still holdouts). Events like these are never truly settled in all their aspects, but The Tale Untwisted promises to be a major force in the ongoing debate.

Friday, January 20, 2023

Review - "The Eighth Connecticut Volunteer Infantry in the Civil War" by Liska & Perlotto

Tuesday, January 17, 2023

Booknotes: The Civil Wars of General Joseph E. Johnston, Volume 1

• The Civil Wars of General Joseph E. Johnston: Confederate States Army - Volume I: Virginia and Mississippi, 1861–1863 by Richard M. McMurry (Savas Beatie, 2023). I don't follow the NBA and MLB much anymore, but way back when I did I was repeatedly baffled by the frequency with which teams recycled the same head coaches and managers, as if giving a known quantity a fresh start immediately after a disastrous recent performance was always less risky than giving someone else their first opportunity. It's not difficult to get the same vibe from the Davis administration's record of handling appointments to Confederate army/theater command. Each being one of Davis's five 1861 appointees to full general, Joe Johnston and PGT Beauregard were constantly shifted around to top jobs throughout the war even though neither proved capable of putting aside ego and personal differences with the CSA president in order to get together on the same page for the good of the cause. In contrast, the US won the Civil War with commanding generals who weren't even on Lincoln's radar when the fighting broke out. Johnston's place in the war has always sparked discussion, with some approving of his Fabian-style conduct of war (exemplified by his 1864 North Georgia campaign) as a possible war-winning antidote to Robert E. Lee's more aggressive, risky, and casualty-intensive style of generalship while others have more persuasively argued that Johnston's way of war was incompatible with achieving both independence and preservation of southern society (slavery in particular being unsustainable if vast swaths of the Confederacy were yielded through trading space for time). The first of two volumes, Richard McMurry's The Civil Wars of General Joseph E. Johnston: Confederate States Army - Volume I: Virginia and Mississippi, 1861–1863 keenly focuses on the consequences of a warring nation's lack of high command unity and purpose. From the description: McMurry's book strongly contends "that the Confederacy’s most lethal enemy was the toxic dissension within the top echelons of its high command. The discord between General Johnston and President Jefferson Davis (and others), which began early in the conflict and only worsened as the months passed, routinely prevented the cooperation and coordination the South needed on the battlefield if it was going to achieve its independence. The result was one failed campaign after another, all of which cumulatively doomed the Southern Confederacy." Obviously, interpersonal relationships within institutions have had a major impact on winning and losing wars throughout history, but the unabated, war-spanning feud between Johnston and Davis was, in the context of the ACW, exceptional in its detrimental consequences. Though focused on that noxious pairing, this book also looks at Johnston's interactions with peer generals. Examining more than just the fratricidal war fought between Davis and Johnston, "McMurry’s study is not a traditional military biography but a lively and opinionated conversation about major campaigns and battles, strategic goals and accomplishments, and how these men and their decision-making and leadership abilities directly impacted the war effort. Personalities, argues McMurry, win and lose wars, and the military and political leaders who form the focal point of this study could not have been more different (and in the case of Davis and Johnston, more at odds) when it came to making the important and timely decisions necessary to wage the war effectively." Capturing Johnston "in a way that has never been accomplished," McMurry "sheds fresh light on old controversies and compels readers to think about major wartime events in unique and compelling ways." The Civil Wars of General Joseph E. Johnston profoundly demonstrates "how qualities of character played an oversized role in determining the outcome of the Civil War." I am very much looking forward to reading both of these volumes.

Monday, January 16, 2023

Booknotes: "Gunboats, Muskets, and Torpedoes: Coastal South Carolina, 1861–1865"

• Gunboats, Muskets, and Torpedoes: Coastal South Carolina, 1861–1865 by Michael G. Laramie (Westholme, 2022). Despite some of its idiosyncrasies [see my review], I rather liked Michael Laramie's Gunboats, Muskets, and Torpedoes: Coastal North Carolina, 1861–1865 (2020). Its very similarly titled companion volume, Gunboats, Muskets, and Torpedoes: Coastal South Carolina, 1861–1865, has just arrived. Unlike the situation in North Carolina, where heavy action occurred all along the state's lengthy and tortuously winding coastline, South Carolina's army-navy clashes rapidly concentrated on the Charleston area. From the description: "While the southern shoreline of the state would be dominated by Union amphibious raids to cut the Savannah-Charleston railroad and the establishment of a Union army and navy facility at Port Royal, the contest for coastal South Carolina burned the brightest at Charleston. One of the primary ports of the Confederacy, the siege of this city would last from early 1863 until the last months of the war." Advancements in military engineering and technology were a major consideration in the North Carolina volume, and those themes carry into this book as well. More from the description: "It was during these operations that the industrial age first introduced elements of modern warfare at a scale that the world noticed. The ironclad, the newest of the wonder weapons, tested its abilities against the naval fortifications and the artillery of the day, while others such as the torpedo boat and the forerunner of generations beyond, the submarine, were demonstrated with stunning effect. Nor were these matters confined to just maritime affairs as the trench warfare, artillery barrages, bombproof shelters, wire obstructions, and one of the first minefields amply demonstrated." While much of the focus is on operations and the military impact of industry and technology, Laramie's narrative never loses sight of the human experience in all its forms. "While these technological changes and the philosophies they spawned are easily discerned today, they are but part of a much larger story; one of ordinary people thrust into extraordinary circumstances. A familiar tale of foolishness and brilliance, of bravery and fear, and of mistakes and opportunity. From the soldiers that crouched in the shaking bombproofs of Fort Wagner and those who flung themselves against this fortress, through the monotonous routine of blockade duty and the incessant artillery duels on both sides, to the bravery of the first Black soldiers who fought for the Union, and those who refused to yield or looked to break the deadlock with a stroke of genius, this is their story."

Thursday, January 12, 2023

Review - "Union General: Samuel Ryan Curtis and Victory in the West" by William Shea

Shea's assessment of Curtis's generalship is laudatory throughout. He is persuasive in seeing, as others have, Curtis's failure to capture Little Rock in 1862 as a product of geographical and logistical limitations beyond his control rather than any particular shortcoming in generalship. Even after being forced to turn away from Little Rock, Curtis's aborted march deep into Arkansas marked a pioneering effort in living off the land (a practice that would assume much grander proportions in later campaigns) and solidified Curtis's position as one of the Union Army's most aggressive-minded commanders of the early-war period. His occupation of Helena, which was quickly established as a fortified base for supporting subsequent downriver operations, also proved significant.

Analyzing Curtis's actions farther west, Shea cites the department commander's measured handling of Great Plains Indian violence as evidence that Sand Creek might not have happened had Curtis not been urgently recalled to Kansas in response to the Price Raid and forced to relinquish military affairs in Colorado to its governor and his appointees. It's speculation, but it's something to consider as a contingent event in the widening Plains conflicts of the Civil War period and beyond.

When Curtis's Arkansas campaign petered out in mid-1862 due to the failure of the White River resupply expedition, he had penetrated deeper south into enemy territory than any other Union general and had proved himself aggressive, highly capable, and willing to take risks—all leadership qualities desperate sought after by the War Department in Washington. So why didn't this early success, which was publicly recognized at the time, not catapult Curtis, either immediately or later on, into the higher echelon of Union Army commanders entrusted with major field commands? There was certainly precedent for Trans-Mississippi officers and generals moving on to bigger and better posts east of the river. Less proven generals such as John Pope and John Schofield were appointed to key commands, and even heavyweights such as Grant and Sheridan started in Missouri, but Curtis always remained behind to head a number of boundary-shifting departments. Indeed, his ultimate "reward" for Westport was command of the Department of the Northwest, a barely lateral (at best) career move that he accurately assessed as a shelving more than anything else. Age undoubtedly played some factor in Curtis being underutilized. He was 56 at the start of the war, which is not old by today's standards of health and fitness (and Curtis was only two years older than Charles F. Smith, a well-respected western theater general long considered Grant's idol). Nevertheless, he was certainly older than generals found on the standard lists of Union Army greats. Sherman uncharitably declared him too old for active service, better suited for an administrative desk job. In the book, Shea reveals Curtis to be fully capable of arduous outdoor service for extended periods of time, though that vibrancy must be balanced against the general's tendency to overexert himself and require recuperative rest periods of a length that perhaps a younger man would not have required. Though the general topic is frequently raised at various times, the narrative struggles to provide a clear picture of the extent of political sponsorship that Curtis might have had in Congress or within the Lincoln administration. Iowa was a Republican stronghold, but it could not have assured the kind of powerful political backing that a promising Midwestern general from Illinois or Ohio might have enjoyed. As has often been mentioned, operating in the most isolated of the war's three major theaters also undoubtedly hindered popular and political recognition of Curtis's achievements. As the book shows, Curtis certainly had no friend in Henry Halleck. Lincoln professed support, though its sincerity remains open to question, and the president didn't seem terribly interested in using his influence to further advance Curtis's career. When abolitionist Curtis was relieved of his command of the Missouri department by Lincoln over the general's friction with the proslavery Unionist governor, the president famously remarked that since he couldn't get rid of the governor he had to get rid of Curtis. Later, when Grant became the general in chief of the army, he did Curtis no favors. Indeed, as others have also failed to discover, the author could not find any source for the apparent antipathy Grant felt toward Curtis almost from the war's get go. Perhaps early-war competition had something to do with it, or it was another example of a Grant grudge that he held on to as tenaciously as he fought his battles, regardless of its undefinable, unjustified, or secondhand-sourced origins. Though Curtis was a West Pointer, perhaps (as Shea suggests as a possibility) his early resignation and prewar career as a multi-term Republican congressman made him more of a political general in Grant's eyes. Who knows. The most controversial episode of Curtis's Civil War career involved allegations of personal involvement in the illegal cotton trade at Helena. Others have examined cotton profiteering among Curtis's officers, but Shea's research found no evidence of any personal malfeasance on Curtis's part. In the end, the author traces corruption allegations directed toward Curtis to designing men in the form of disappointed civilian speculators and ideologically opposed politicians and military officers (particularly the latter group). Shea concedes that Curtis displayed insufficient oversight over the entire process of cotton regulation (a rare misstep from a more typically scrupulous administrator), but laments the fact that the lengthy court of inquiry, which concluded in June 1863 finding no justification for recommending court martial proceedings, sidelined such a useful general for a year during the war's critical middle period. Shea very lightly touches upon another matter of some controversy. Curtis was always a hardliner when it came to dealing with guerrillas, and that attitude hardened further when beloved son Henry was killed by Quantrill's men at Baxter Springs. As noted in the book, the U.S. attorney in Colorado complained about Curtis's summary execution of prisoners, but the general dismissed those legal concerns and continued the practice in Missouri with captured members of Price's command during the 1864 campaign there. An argument could be made that the issue is worthy of a deeper look than the passing mention it gets in this biography. At the close of the conflict, Curtis stayed highly active. He cast aside the disappointment he felt with the War Department's seeming lack of due regard for his contributions to Union victory, and accepted the arduous, and rather thankless, task of traveling to the frontier to lay the initial groundwork for lasting treaties with the Plains tribes. With a nod to his prewar sponsorship of the original Pacific railroad bill, Curtis was offered, and he accepted, a lucrative position as a transcontinental railroad commissioner. He was still doing railroad work when he died (likely from a stroke) the day after Christmas in 1866. Indeed, as Shea argues, death so soon after the war ended very likely contributed mightily to Curtis's rapid disappearance from the general public's imagination. In addition to spending his entire Civil War service in the most isolated of the conflict's three primary fighting theaters, the general had no opportunity to publish his own story or otherwise participate in the many public debates that kept prominent Civil War generals in the public eye for decades. Highly celebratory while remaining judicious, William Shea's Union General is a fine biography that should go a long way toward fostering a wider recognition and appreciation of Samuel Ryan Curtis's substantial historical legacy.Notes:

* - There are others, but mainstays included Shea's own (with co-author Earl Hess) Pea Ridge: Civil War Campaign in the West (1992)—which would take a monumental effort to supplant, Robert Schultz's The March to the River: From the Battle of Pea Ridge to Helena, Spring 1862 (2014), Howard Monnett's Action Before Westport, 1864 (1964,R-1995), and Kyle Sinisi's The Last Hurrah: Sterling Price's Missouri Expedition of 1864 (2015). Michael Banasik's Embattled Arkansas (1996) [the early sections of which examine Curtis's 1862 campaign in NE Arkansas], Christopher Wehner's The 11th Wisconsin in the Civil War (2008) [which offers good information on Cache River and cotton corruption among officers in Curtis's command], and A Severe and Bloody Fight: The Battle of Whitney's Lane and Military Occupation of White County, Arkansas, May and June 1862 (1996) by Akridge & Powers are somewhat puzzling absences from the Union General bibliography, the last perhaps even more so given the effusive back cover blurb Shea gave it.

Wednesday, January 11, 2023

Booknotes: The Military Memoirs of a Confederate Line Officer

• The Military Memoirs of a Confederate Line Officer: Captain John C. Reed’s Civil War from Manassas to Appomattox edited by William R. Cobb (Savas Beatie, 2023). From the description: "John C. Reed fought through the entire war as an officer in the 8th Georgia Infantry [Company I], most of it with General Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia." His unit also campaigned in East Tennessee, the 8th unsuccessfully assaulting Fort Sanders with their comrades of G.T. Anderson's Brigade. "The Princeton graduate was wounded at least twice (Second Manassas and Gettysburg), promoted to captain during the Wilderness fighting on May 6, 1864, and led his company through the balance of the Overland Campaign, throughout the horrific siege of Petersburg, and all the way to the Appomattox surrender on April 9, 1865." Foreword contributor Henry Persons, Lt. Col. (ret.) praises Reed's memoir for the "rich and compelling accounts of his regiment's actions and those of its sister units." Reed's First Manassas account (the 8th was part of Bartow's Brigade) is singled out by Persons for its exceptional detail and accuracy. In addition to being accompanied by a really special hand-drawn map, Reed's account also "corrects the errors in Gen. Joe Johnston's report of the regiment's actions at Mathew's Hill." You might recall Harry Smeltzer's recent addition of the Reed account and map to his invaluable First Bull Run digital archive [here]. Editor William Cobb precedes the memoir material with a brief general introduction, and he footnotes Reed's text throughout. The notes largely consist of biographical sketches of individuals mentioned in the text, but you'll also find explanations of Reed's literary allusions, some unit sketches, event descriptions, military definitions, etc. Cobb also commissioned 9 maps for the project, a fine-looking combo set from Hampton Newsome (hey, he's a pretty good cartographer, too) and Hal Jesperson.

Tuesday, January 10, 2023

Booknotes: A Nation So Conceived

• A Nation So Conceived: Abraham Lincoln and the Paradox of Democratic Sovereignty by Michael P. Zuckert (UP of Kansas, 2023). This book is part of University Press of Kansas's Constitutional Thinking series, the volumes of which "develop constitutional theory beyond legalistic concerns by examining such matters as institutional development; public policy; and political behavior, culture, and theory." In A Nation So Conceived author Michael Zuckert "argues for a coherent center to Lincoln’s political ideology, a core idea that unifies his thought and thus illuminates his deeds as a political actor. That core idea is captured in the term “democratic sovereignty.” Zuckert provides invaluable guidance to understanding both Lincoln and the politics of the United States between 1845 and Lincoln’s death in 1865 by focusing on roughly a dozen speeches that Lincoln made during his career. This reader-friendly chronological organization is motivated by Zuckert’s emphasis on Lincoln as a practical politician who was always fully aware of the political context of the moment within which he was speaking." Through the lens of Lincoln's speeches, the book examines the "paradoxical duality" of one of the central doctrines of American political thought: "created equal." More from the description: "According to Lincoln’s speech at Gettysburg, America was new precisely because it was born in dedication to the first premise of the theory of democratic sovereignty: that all men are created equal. Lincoln’s thought consisted in an ever-deepening meditation on the grounds and implications of that proposition, both in its constructive and in its destructive potential. The goodness of the American regime is derived from that ground and the chief dangers to the regime emanate from the same soil." Zuckert's study reveals how Lincoln understood that duality and explains "how his deeds as a political actor constituted a therapy aimed at" addressing its particular "pathological consequences." In reexamining Lincoln's speeches between 1838 and 1865, endurance of the nation and its political institutions emerges as a primary concern, and Zuckert sees the source of it in Lincoln's worries over the consequences of the duality referred to above. In the author's view, "(t)he problem of perpetuation loomed so large for Lincoln because he considered that proposition, [that all men are created equal] properly adumbrated, to capture the true foundation of political right but at the same time to be the sources of various threats to the survival of the regime" (pg. 1).

Monday, January 9, 2023

Booknotes: From the Mountains to the Bay

• From the Mountains to the Bay: The War in Virginia, January-May 1862 by Ethan S. Rafuse (UP of Kansas, 2023). Ethan Rafuse's From the Mountains to the Bay "is the only modern scholarly work that looks at the operations that took place in Virginia in early 1862, from the Romney Campaign that opened the year to the naval engagement between the Monitor and Merrimac to the movements and engagements fought by Union and Confederate forces in the Shenandoah Valley, on the York-James Peninsula, and in northern Virginia, as a single, comprehensive campaign." As referenced above, offensive land and river actions in the Virginia theater were conducted along five major lines of operation during the first five months of 1862. More from the description: "In the course of these operations, the North demonstrated it had learned quite a bit from its setbacks of 1861 and was able to achieve significant operational and tactical success on both land and sea. This enabled Union arms to bring a considerable portion of Virginia under Federal control—in some cases temporarily and in others permanently. Indeed, at points during the spring and early summer of 1862, it appeared the North just might succeed in bringing about the defeat of the rebellion before the year was out." As recalled by the author in the preface, this project began as a brief overview of the interconnected Peninsula and Valley campaigns of 1862. That initial synthesis approach was later expanded to a wider treatment of the January-May period. Interestingly, though actions through July 1862 are mentioned in the publisher's description and Rafuse duly references the two months following May as housing key transformative events, neither preface nor epilogue directly reveal any intentions toward publishing a June-July follow up to this "single stand-alone" volume. On the other hand, life has a nasty habit of disrupting intentions and being cagey about future plans is often appropriate.

Friday, January 6, 2023

2022 A.M. Pate Award winner

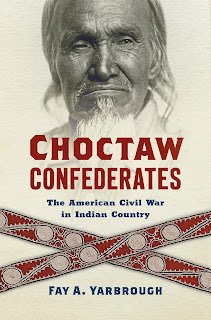

Formal unit histories of Union and Confederate Indian battalions and regiments, many of which endured long service, continue to be an untapped category of modern Civil War publishing. Only one full-length study exists, 1989's The Confederate Cherokees: John Drew's Regiment of Mounted Rifles, which was reissued in 2017 with a new preface. That regiment was short lived as a unit, its greater portion deserting in late 1861. Scarce source material written by the men in the ranks is always going to make the job difficult, but Yarbrough's selective investigation of various aspects of the First Choctaw and Chickasaw regiment and Jane Johansson's Albert C. Ellithorpe, the First Indian Home Guards, and the Civil War on the Trans-Mississippi Frontier (2016) tentatively suggest that Indian regimental histories are possible if the author is willing to get more creative than usual.

Though Choctaw Confederates would have been a top contender in any year, it was pretty slim pickings in 2022 for those interested in Trans-Mississippi Civil War topics. The campaign and battle history landscape in particular has dried up over recent years. Hopefully, we're just in the middle of a temporary rough patch.

Wednesday, January 4, 2023

Review - "Lady Rebels of Civil War Missouri" by Larry Wood

Monday, January 2, 2023

Booknotes: Shantyboats and Roustabouts

• Shantyboats and Roustabouts: The River Poor of St. Louis, 1875–1930 by Gregg Andrews (LSU Press, 2022).

Before its post-Civil War decline, steamboat commerce up and down the Mississippi River was an economic powerhouse that served vast expanses of the trans-Appalachian West, and the riverfronts of major cities such as Memphis and New Orleans were hotbeds of that activity. On the other hand, those same vitally important riverfront zones were socially stigmatized as dangerous dens of crime and vice best avoided by "respectable" citizens after dark. Civil War units recruited from such places often earned reputations as fierce fighters and just as feared troublemakers. Wheat's Special Battalion, its ranks heavily filled with a diverse array of New Orleans misfits and wharf rats, is a prime example.

Before its post-Civil War decline, steamboat commerce up and down the Mississippi River was an economic powerhouse that served vast expanses of the trans-Appalachian West, and the riverfronts of major cities such as Memphis and New Orleans were hotbeds of that activity. On the other hand, those same vitally important riverfront zones were socially stigmatized as dangerous dens of crime and vice best avoided by "respectable" citizens after dark. Civil War units recruited from such places often earned reputations as fierce fighters and just as feared troublemakers. Wheat's Special Battalion, its ranks heavily filled with a diverse array of New Orleans misfits and wharf rats, is a prime example.