By most estimates, journalist and War Department official Charles Anderson Dana had a significant personal impact on the course of the American Civil War and on the careers of key generals and politicians. But just how influential was he? In assessing the effects of the background influencers of history, the potential for encountering frustrating pitfalls can be high. The nature of advice offered to those in power often goes undocumented (though that can't really be said for Dana) or is disputed, and decision-makers tend to jealously hoard credit when success is involved. Close access to power also breeds friends and enemies alike, and the earnestness of both groups can cloud the historical picture in equal measure. Taking all that into account, Carl Guarneri's deeply researched, insightful, and powerfully argued Lincoln's Informer: Charles A. Dana and the Inside Story of the Union War clearly offers Civil War students the most complete picture yet available of the depth and range of Dana's personal involvement in numerous aspects of the Union war effort.

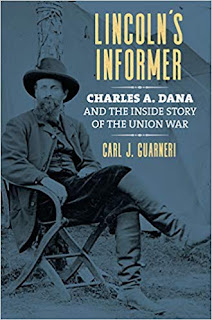

By most estimates, journalist and War Department official Charles Anderson Dana had a significant personal impact on the course of the American Civil War and on the careers of key generals and politicians. But just how influential was he? In assessing the effects of the background influencers of history, the potential for encountering frustrating pitfalls can be high. The nature of advice offered to those in power often goes undocumented (though that can't really be said for Dana) or is disputed, and decision-makers tend to jealously hoard credit when success is involved. Close access to power also breeds friends and enemies alike, and the earnestness of both groups can cloud the historical picture in equal measure. Taking all that into account, Carl Guarneri's deeply researched, insightful, and powerfully argued Lincoln's Informer: Charles A. Dana and the Inside Story of the Union War clearly offers Civil War students the most complete picture yet available of the depth and range of Dana's personal involvement in numerous aspects of the Union war effort.As its title suggests, Guarneri's biographical study of Dana is centered on the Civil War years. However, the author well recognizes how essential Dana's prewar personal and professional experiences were in shaping how the military novice would carry out his new War Department responsibilities during the upcoming conflict. In highly informative fashion, the book's early chapters fulfill the important background role of establishing the character development, uncompromising Radical Republican credentials, and managerial capabilities that would all serve Dana so well later on. After an abbreviated Harvard education, Dana lived in and helped administer a utopian collective community, and his business instincts and personnel management skills were major factors behind the commercial success of Horace Greeley's New York Tribune (of which Dana served as managing editor). Guarneri perceptively traces much of Dana's adroitness in getting along with the notoriously irascible War Secretary Edwin Stanton to his successful professional partnership with the mercurial Greeley. At the Tribune, Dana was able to express his own editorial voice (one that often clashed with Greeley's notorious flip-flopping on big issues) without alienated his boss or grossly exceeding the boundaries of subordinate behavior. This tactful professionalism helped him be his own man at the War Department without drawing the ire of Stanton, with whom he maintained cordial relations. Maturity in successfully navigating delicate subordinate relationships also allowed Dana, whose War Department investigations in the West uncovered trade violations and army contract frauds committed by Lincoln friends and political allies, to force the president's hand without making the chief executive his enemy.

Dana would ultimately be fired by Greeley in 1862, an act Guarneri attributes more to investor/board pressure than Greeley's own personal animus. Though Dana was frequently critical of how the war was managed up to that point, the administration nevertheless saw the newly unemployed journalist as a useful friend, and Stanton quickly secured Dana's employment as a special agent for investigating fraud in the West. There he would meet the Civil War military figure with whom he would become most closely associated, U.S. Grant. Later, as a "special commissioner" nominally assigned to see to army paymasters but really the administration's representative (or "spy" as some would maintain) in Grant's headquarters during the Vicksburg Campaign, Dana would become a key player in Grant's rise. Of course, the story of Dana's arrival, the warm rapport that developed quickly between he and Grant, and the highly positive impression of Grant's character and generalship that Dana's War Department reports created in Washington have already been explored in countless publications, but one can make a very strong argument that Guarneri's detailed and judicious assessment of the Grant-Dana relationship is the most comprehensive now available in the literature.

Far more than Grant's cheerleader, the Dana of Guarneri's study was a close adviser to Grant and a very useful go-between that could get Grant what he needed while shielding the general himself from being seen as the source of incessant manpower and resource demands. Dana's long, detailed reports to Stanton regarding the campaign's progress relieved Grant of a significant burden as well. Grant and Dana's shared views regarding the big issues of the war and how the conflict should be fought made the general easy to champion, but Guarneri also astutely notes that this growing personal loyalty seldom meant that the War Department was ill-served in the bargain. That's not to say Washington was never deceived, as Dana participated in the cover-up of Grant's infamous "Yazoo bender." While the author does not dwell upon the point, it also seems highly likely that Dana's powers of persuasion, sharply honed through his partisan Tribune editorials, gave his pro-Grant correspondence a hearty measure of added impact.

A lesser appreciated aspect of Dana's official correspondence can be found in his detailed 'report cards' of Grant's staff and subordinates. Though personal grudges interfered in some of these assessments, and he wrote negative recommendations of several generals that modern historians consider quite capable (ex. Francis Herron and A.J. Smith), the author credits these reports with heavily influencing subsequent War Department personnel promotions and assignments.

Of course, the other major Civil War general closely associated with Dana is William S. Rosecrans. Dana has often been assigned a lion's share of the blame for Rosecrans's dismissal, his reports comprising a constant stream of negative distortions regarding Rosecrans's mindset and actions in the wake of the Chickamauga disaster. Guarneri counters complaints of Dana's bias against Rosecrans by pointing out that there were some positive reports interspersed with the negative ones, but the author clearly feels that the end result justified the means in Rosecrans's case. If providing a less than evenhanded picture was necessary to get the point across to the remaining Rosecrans supporters in the administration that the general's fighting spirit was insufficient and the army needed to be saved by his replacement, then Guarneri sees that as no major miscarriage of justice (with ensuing events proving Dana correct in his views). While that will not please Rosecrans's supporters, and more recent scholarship has suggested that Rosecrans was not quite the shattered individual of the older historical record, it remains the case that the way the army was handled after the change in command succeeded beyond all expectation.

After spending time in Washington after the victory at Chattanooga, Dana rejoined Grant in the field for the Overland Campaign. While he resumed his old course of sustaining Grant, some doubts began to creep into his mind. Even so, though critical thoughts regarding Grant's strategic and tactical approaches to the Virginia campaign and what he saw as excessive reluctance to relieve underperforming generals (Dana wanted both Meade and Butler to go) emerged, their substance was either covered up in reports or heavily moderated. In pointing out that there was no one in the army above Grant to appeal to and undermining the general in the minds of those at the top (i.e. Lincoln and Stanton) might lead to his dismissal, Guarneri argues with some merit that the public good (namely, the catastrophic effect that Grant's firing could have had on the overall war effort) was best advanced by Dana's judicious self-censorship.

The book's main title is apt in many ways, but it might even be more appropriately phrased "Stanton's Fireman." When Dana, who started out as Stanton's special agent before being appointed Asst. Secretary of War, wasn't in the field he was in a War Department office working as hard as his boss. The book documents many special tasks that were assigned by Stanton specifically to Dana. In addition to already mentioned contraband trade and contract investigations, other jobs include post-riot oversight of the draft in New York, a spymaster post, and being the go-to man at the War Department for overseeing complex logistical operations. Dana also served as a partisan political operative during the 1864 election cycles, providing an official stamp to propaganda that inflated the strength and influence of the Midwest Copperhead movement. In an even more troubling blow to honest government, Dana earnestly participated in War Department directives aimed at promoting the Republican vote and suppressing the Democratic vote in both the army and on the home front. The author also identifies Dana as a key figure in the behind-the-scenes lobbying (a.k.a. bribing through patronage promises) of Democratic votes for the passage of the 13th Amendment. Overall, the author builds a persuasive case that Dana deserves much higher recognition as an important contributor to Union victory and emancipation.

After the war, Dana set himself to returning to New York newspaper journalism. Denied the opportunity to purchase Republican papers, he turned to New York's Sun, which had a substantial Democratic reader base. Though he editorially supported Grant's presidential election, Dana altered his focus from promoting Radical Reconstruction and the political rights and welfare of former slaves to exposing public corruption. Though he appears to have had a longstanding ideological disposition that judged freedpeople better left to their own devices without excessive government intervention into their affairs, his break with Grant was most shocking. Guarneri traces it to Grant's refusal to appoint Dana to the lucrative post of customs collector of the port of New York, one of the richest patronage plums. It seems that Grant had heard about Dana's mild criticisms of his Overland & Petersburg campaigns and never forgave him for it. While this cannot be definitively proven as the root cause, the author argues that both the timing and the established pattern in Grant's character of punishing criticism (no matter how muted) as unforgivable disloyalty fit the situation. The author also appropriately notes the human irony inherent in Dana's public campaigning against nepotism and cronyism in government while at the same time constantly seeking those kinds of rewards for himself. However, none of these political transformations and personal disappointments greatly hindered a second career in journalism that was a huge success. The book also discusses the writing and publication of Dana's Recollections of the Civil War, which was ghostwritten in first person by Ida Tarbell and remains a cautiously oft-used historical source.

Charles A. Dana is far from a shadowy and forgotten Civil War figure, even general Civil War readers probably have at least a passing familiarity with his War Department role (particularly his association with Grant) and antislavery journalism, but Carl Guarneri's Lincoln's Informer is unprecedented in how expansively it defines and details the depth of Dana's myriad of important influences and actions. Often hailed on one side as a just promoter of talented men that would see the Union cause to victory and a vicious libeler on the other, Dana, through the determined efforts of Guarneri's fine scholarship, can now be more widely appreciated not just as an influential go-between but as an important historical actor in his own right. Highly recommended.

Please elaborate and/or direct us to a discussion of the "cover-up" of Grant's alleged "Yazoo bender."

ReplyDeleteIn Dana's case, he simply didn't report it to Stanton and denied Grant was drunk during the river trip until after Grant's death. Vicksburg studies and all major Grant bios discuss the incident, with divergent opinions offered regarding sources and details. Most recently, a reader pointed me toward Donald Miller's short synthesis and commentary about it in his 2019 book "Vicksburg." After reading it, I agree with him that the section is commendable as one of the more judicious and level-headed assessments of the controversy.

Delete