**NEW RELEASES1** Scheduled for AUG 2021:

• Theater of a Separate War: The Civil War West of the Mississippi River, 1861–1865 by Thomas Cutrer.

• The Horse at Gettysburg: Prepared for the Day of Battle by Chris Bagley.

• General John A. Rawlins: No Ordinary Man by Allen Ottens.

• Escape!: The Story of the Confederacy's Infamous Libby Prison and the Civil War's Largest Jail Break by Robert Watson.

• "We Gave Them Thunder": Marmaduke’s Raid and the Civil War in Missouri and Arkansas by Piston & Rutherford.

• Crosshairs on the Capital: Jubal Early’s Raid on Washington, D.C., July 1864 - Reasons, Reactions, and Results by James Bruns.

• Ohio at Antietam: The Buckeye State’s Sacrifice on America’s Bloodiest Day by Pawlak & Welch.

• Our Comfort in Dying: Civil War Sermons by R. L. Dabney, Stonewall Jackson’s Chief-of-Staff edited by Jonathan Peters.

Comments: I received a very early copy of the Piston & Rutherford book and have reviewed it already (to read my thoughts on it go here). I've also previously commented upon the much-welcome revised edition of Theater of a Separate War at this link. I suspect that many readers will be interested in the Rawlins biography.

1 - These monthly release lists are not meant to be exhaustive compilations of non-fiction releases. They do not include non-revised/expanded reprints of previously published books and digital-only titles. Works that only tangentially address the war years and those not reviewable are also generally excluded. Inevitably, one or more titles on this list will get a rescheduled release (and they do not get repeated later), so revisiting the past few "Coming Soon" posts is the best way to pick up stragglers.

Friday, July 30, 2021

Tuesday, July 27, 2021

Booknotes: Southern Strategies

New Arrival:

• Southern Strategies: Why the Confederacy Failed edited by Christian B. Keller (UP of Kansas, 2021). Ultimately, the Confederacy collapsed because it was defeated militarily by the US, and numerous books, book chapters, and articles have been devoted to explaining the many internal and external factors (both on and off the battlefield) that contributed to that result. Edited by Christian Keller, the director of the US Army War College's Military History Program, the six essays in Southern Strategies: Why the Confederacy Failed adds to that existing body of work by applying a new framework of analysis. Its series of discussions comprise "the first-ever analysis of Confederate defeat using the lenses of classical strategic and leadership theory. The contributors bring over one hundred years of experience in the field at the junior and senior levels of military leadership and over forty years of teaching in professional military education. Well-aware that the nature of war is immutable and unchanging, they combine their firsthand experience of this truth with solid scholarship to offer new theoretical and historical perspectives about why the South failed in its bid for independence." The essays selectively reexamine a number of ways in which the Confederacy was responsible for its own demise. More from the description: "The contributors identify and analyze the mistakes made by the Confederate political and strategic leadership that handicapped the prospects for independence and placed immense pressure on Confederate military commanders to compensate on the battlefield for what should have been achieved by other instruments of national power. These instruments are the diplomatic, informational (including intelligence and public morale), and economic aspects of a nation's capability to exert its will internationally. When combined with military power, the acronym DIME emerges, a theoretical tool that offers historians and national security professionals alike a useful method to analyze how a state, such as the Union, the Confederacy, or the modern United States, wielded or currently wields its power at the strategic level." Half of the chapters enter specific campaigns into the discussion (the 1862 Valley Campaign, the 1862 Maryland Campaign, and the 1863 Gettysburg Campaign), while the rest look that the flaws in Confederate economic/financial policy, diplomacy, and Trans-Mississippi strategy. "Each essay examines how well rebel strategic leaders employed and integrated these instruments, given that the seceded South possessed enough diplomatic, informational, military, and economic power to theoretically win its independence. The essayists also apply the ends-ways-means model of analysis to each topic to offer readers greater insight into the Confederate leadership's challenges." Reminding readers that the issues behind Confederate failure were complex and numerous, Southern Strategies "offers fresh and theoretically novel interpretations at the strategic level that open new doors for future research." It is also hoped that the volume "will increase public interest in the big questions surrounding Confederate defeat."

• Southern Strategies: Why the Confederacy Failed edited by Christian B. Keller (UP of Kansas, 2021). Ultimately, the Confederacy collapsed because it was defeated militarily by the US, and numerous books, book chapters, and articles have been devoted to explaining the many internal and external factors (both on and off the battlefield) that contributed to that result. Edited by Christian Keller, the director of the US Army War College's Military History Program, the six essays in Southern Strategies: Why the Confederacy Failed adds to that existing body of work by applying a new framework of analysis. Its series of discussions comprise "the first-ever analysis of Confederate defeat using the lenses of classical strategic and leadership theory. The contributors bring over one hundred years of experience in the field at the junior and senior levels of military leadership and over forty years of teaching in professional military education. Well-aware that the nature of war is immutable and unchanging, they combine their firsthand experience of this truth with solid scholarship to offer new theoretical and historical perspectives about why the South failed in its bid for independence." The essays selectively reexamine a number of ways in which the Confederacy was responsible for its own demise. More from the description: "The contributors identify and analyze the mistakes made by the Confederate political and strategic leadership that handicapped the prospects for independence and placed immense pressure on Confederate military commanders to compensate on the battlefield for what should have been achieved by other instruments of national power. These instruments are the diplomatic, informational (including intelligence and public morale), and economic aspects of a nation's capability to exert its will internationally. When combined with military power, the acronym DIME emerges, a theoretical tool that offers historians and national security professionals alike a useful method to analyze how a state, such as the Union, the Confederacy, or the modern United States, wielded or currently wields its power at the strategic level." Half of the chapters enter specific campaigns into the discussion (the 1862 Valley Campaign, the 1862 Maryland Campaign, and the 1863 Gettysburg Campaign), while the rest look that the flaws in Confederate economic/financial policy, diplomacy, and Trans-Mississippi strategy. "Each essay examines how well rebel strategic leaders employed and integrated these instruments, given that the seceded South possessed enough diplomatic, informational, military, and economic power to theoretically win its independence. The essayists also apply the ends-ways-means model of analysis to each topic to offer readers greater insight into the Confederate leadership's challenges." Reminding readers that the issues behind Confederate failure were complex and numerous, Southern Strategies "offers fresh and theoretically novel interpretations at the strategic level that open new doors for future research." It is also hoped that the volume "will increase public interest in the big questions surrounding Confederate defeat."

Sunday, July 25, 2021

Booknotes: A Notable Bully

New Arrival:

• A Notable Bully: Colonel Billy Wilson, Masculinity, and the Pursuit of Violence in the Civil War Era by Robert E. Cray (Kent St UP, 2021). With a name as indistinctive as Billy Wilson I suppose it is very easy to encounter it more than once somewhere and not have it stick. It doesn't ring any clear bells with me; however, according to his new biographer Robert Cray (not Strong Persuader Robert Cray), Wilson was a very prominent New York figure for much of the mid-nineteenth century. From the description of Cray's A Notable Bully: "Largely forgotten by historians, Billy Wilson (1822–1874) was a giant in his time, a man well known throughout New York City, a man shaped by the city’s immigrant culture, its harsh voting practices, and its efforts to participate in the War for the Union. For decades, Wilson’s name made headlines―for many different reasons―in the city’s major newspapers." As the subtitle suggests, violence was a major part of Wilson's persona and public life. "An immigrant who settled in New York in 1842, Wilson found work as a prizefighter, a shoulder hitter, an immigrant runner, and a pawnbroker, before finally entering politics and being elected an alderman." With so many Zouave companies and regiments raised by both sides, it would be unfair to generalize as to their nature, but a number of prominent units contributed to an outward impression that they attracting a certain class of undesirables who resisted discipline more than the typical Civil War volunteer regiment. Unlike some leaders (Louisiana's Roberdeau Wheat being one) who could effectively channel that volatility on and off the battlefield into military usefulness, Wilson was a poor candidate for such a tall task. More from the description: "He harnessed his tough persona to good advantage, in 1861 becoming a colonel in command of a regiment of alleged toughs and ex-convicts known as the “Wilson Zouaves.” A poor disciplinarian, however, Wilson exercised little control over his soldiers, and in 1863, unable to maintain order, he was jailed for a number of weeks. Nonetheless, Wilson returned home to a hero’s welcome that year." Many Civil War-era figures make it hard on potential biographers. "Wilson left behind no personal papers, journals, or correspondences, so Robert E. Cray has masterfully woven together a record of Wilson’s life using the only available records: newspaper stories." Though one might imagine the ways in which reliance on newspaper stories can present problems of their own, you work with what you have, and "(t)hese accounts present Wilson as a fascinating but highly unlikable man. As Cray demonstrates, Wilson bullied his way into New York, bullied his way into fame and politics, and attempted to bully his way into military greatness. The book should have a lot of crossover appeal for those interested in Wilson himself, Civil War history, midcentury New York City immigrant politics and culture, and Civil War-era political violence.

• A Notable Bully: Colonel Billy Wilson, Masculinity, and the Pursuit of Violence in the Civil War Era by Robert E. Cray (Kent St UP, 2021). With a name as indistinctive as Billy Wilson I suppose it is very easy to encounter it more than once somewhere and not have it stick. It doesn't ring any clear bells with me; however, according to his new biographer Robert Cray (not Strong Persuader Robert Cray), Wilson was a very prominent New York figure for much of the mid-nineteenth century. From the description of Cray's A Notable Bully: "Largely forgotten by historians, Billy Wilson (1822–1874) was a giant in his time, a man well known throughout New York City, a man shaped by the city’s immigrant culture, its harsh voting practices, and its efforts to participate in the War for the Union. For decades, Wilson’s name made headlines―for many different reasons―in the city’s major newspapers." As the subtitle suggests, violence was a major part of Wilson's persona and public life. "An immigrant who settled in New York in 1842, Wilson found work as a prizefighter, a shoulder hitter, an immigrant runner, and a pawnbroker, before finally entering politics and being elected an alderman." With so many Zouave companies and regiments raised by both sides, it would be unfair to generalize as to their nature, but a number of prominent units contributed to an outward impression that they attracting a certain class of undesirables who resisted discipline more than the typical Civil War volunteer regiment. Unlike some leaders (Louisiana's Roberdeau Wheat being one) who could effectively channel that volatility on and off the battlefield into military usefulness, Wilson was a poor candidate for such a tall task. More from the description: "He harnessed his tough persona to good advantage, in 1861 becoming a colonel in command of a regiment of alleged toughs and ex-convicts known as the “Wilson Zouaves.” A poor disciplinarian, however, Wilson exercised little control over his soldiers, and in 1863, unable to maintain order, he was jailed for a number of weeks. Nonetheless, Wilson returned home to a hero’s welcome that year." Many Civil War-era figures make it hard on potential biographers. "Wilson left behind no personal papers, journals, or correspondences, so Robert E. Cray has masterfully woven together a record of Wilson’s life using the only available records: newspaper stories." Though one might imagine the ways in which reliance on newspaper stories can present problems of their own, you work with what you have, and "(t)hese accounts present Wilson as a fascinating but highly unlikable man. As Cray demonstrates, Wilson bullied his way into New York, bullied his way into fame and politics, and attempted to bully his way into military greatness. The book should have a lot of crossover appeal for those interested in Wilson himself, Civil War history, midcentury New York City immigrant politics and culture, and Civil War-era political violence.

Wednesday, July 21, 2021

Review - "Campaign for the Confederate Coast: Blockading, Blockade Running and Related Endeavors During the American Civil War" by Gil Hahn

[Campaign for the Confederate Coast: Blockading, Blockade Running and Related Endeavors During the American Civil War by Gil Hahn (West 88th Street Press, 2021). Softcover, tables, notes. Pages main/total:255/313. ISBN:978-1-7349537-0-1. $21.95]

The fact that reasonably swift steamships stood an excellent chance of successfully running the US Navy's blockade of southern ports throughout the Civil War has led many critics to question its role in Union victory and the wisdom of the massive expenditures in men and resources devoted to it. However, others have more persuasively argued that the blockade imposed more than enough hardships upon an already overmatched Confederacy to have a major impact on its defeat. In full agreement with the latter view as well as providing a very broad survey of the blockade and coastal war from US, Confederate, and neutral European perspectives is Gil Hahn's Campaign for the Confederate Coast: Blockading, Blockade Running and Related Endeavors During the American Civil War.

Written in popular fashion, the book offers a rather unusually comprehensive summary of related topics and events that should appeal to a wide range of readers. Avid students of Civil War naval affairs will benefit from the collective reinforcement of their prior reading through Hahn's able synthesis, and those new to the subject matter are exposed to an introductory history with remarkable range. Discussed in the volume are issues of overall strategy; the evolution of the ships, tactics, and technologies employed by each side to either facilitate or hinder blockade running; blockade logistics; and port defenses (in the context of how they aided blockade running).

As is appropriate, the international dimensions of the blockade and blockade running are also addressed at some length. The key roles assumed by European (primarily British) ships, crews, ship builders, and port facilities in trade with the seceded states are well outlined. Hahn does a fine job of summarizing the legal rights of neutrals under mid-nineteenth century international law when it came to overseas trade in times of war. He explains the many ways in which the primary stakeholders—the US, the Confederacy, and Europe (primarily Britain and France)—all jealously guarded their respective belligerent or neutral rights in the present while also attempting to manipulate those same laws in ways that might establish favorable precedents for possible future conflicts.

What proved to be by far the most effective means of blockade enforcement was the capture of ports, and a large section of the book is comprised of a solid chronological history (in four-month intervals) of combined military operations along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts. Aided by a helpful tabulation of blockade running attempts, successes, and losses at each major port over those intervals, readers can clearly see in detail how port seizures (along with temporary or permanent closures) affected the scale and overall distribution of blockade running traffic. For example, tables confirm that Charleston was by far the most important blockade running port over the first half of the war. While the concentrated effort made to capture the city outright in 1863 failed, the attacks did succeed in forcing trade north to Wilmington (though runners did return to Charleston in increasing numbers once Union authorities transferred army and navy resources en masse to other fronts).

Some expected features are missing from the book. While the author very effectively employs a great number of data tables to supplement the text and convey important information, there are no maps. The notes indicate a solid reliance on primary sources, but there is no bibliography and the numberless endnote system employed is rather reader unfriendly when it comes to tracing citations. The volume also lacks an index.

Critics of the Union blockade who cite mere success rate numbers to point out its intractable porousness often tend to inadequately appreciate what the blockade did do through its mere existence. The announcement of the blockade in 1861 caused ordinary trade to cease and commerce at southern ports immediately plunged, never to come anywhere close to regaining prewar levels. As Hahn and many other writers before him have argued, offering the Confederacy, through the lack of a serious blockade, substantially greater freedom to exchange cotton for war materials of all kinds would clearly have narrowed a wide resource gap that, as it stood historically, already took four long years of bitter warfare to exploit for total victory.

Proponents of the "never for want of arms" argument tend to diminish the very real deficiencies Confederate armies as a whole possessed in weapons technology and in the quality and quantity of fixed ammunition, and the problem steadily worsened the further west one looked. Even in the highly prioritized eastern theater, it was the war's midpoint before the Army of Northern Virginia—through captures, production, and importation—could fully modernize its shoulder arms and artillery (and the western and Trans-Mississippi armies never did reach that level). The lack of a strong blockade would clearly have both widened and sped up that process.

Hahn puts it well in saying that "(b)lockading prevented an adequate supply from becoming ample," (pg. 255), and one can reasonable argue that that difference might have tipped the scales. Among other things, Hahn might also have mentioned the blockade's effect on home front morale, where shortages of both luxuries and necessities were felt almost immediately and only worsened as the war progressed. Though the South benefited from high cotton prices, that in no way compensated for the domestic pricing inflation that the blockade materially contributed to and the demoralizing black market economy that made even common items, when available in limited amounts, unaffordable to most civilians. Depending on the degree to which one believes the war's outcome to have been a near-run thing, the book's logical conclusion that "(a) better supplied Confederacy would have been stronger and more resilient, and changed conditions might have changed the course of history" is difficult to refute.

Monday, July 19, 2021

Booknotes: Strategies of North and South

New Arrival:

• Strategies of North and South: A Comparative Analysis of the Union and Confederate Campaigns by Gerald L. Earley (McFarland, 2021). From the description: "Since the Antebellum days there has been a tendency to view the South as martially superior to the North. In the years leading up to the Civil War, Southern elites viewed Confederate soldiers as gallant cavaliers, their Northern enemies as mere brutish inductees. "An effort to give an unbiased appraisal," Strategies of North and South: A Comparative Analysis of the Union and Confederate Campaigns "investigates the validity of this perception, examining the reasoning behind the belief in Southern military supremacy, why the South expected to win, and offering an cultural comparison of the antebellum North and South. The author evaluates command leadership, battle efficiency, variables affecting the outcomes of battles and campaigns, and which side faced the more difficult path to victory and demonstrated superior strategy." The book begins with a pair of chapters that examine antebellum and secession period perceptions of the martial prowess and traditions of each section. This is followed by a year by year analysis of campaigns and battles "with a view of delivering a non-biased assessment of performance as well as outcomes" that "takes into account the challenges and circumstances encountered during the course of the war" (pg. 2). The author readily admits that his approach (campaigns are selected "based on their relevance to the book's objective") is "inherently subjective." It's still unclear from reading the preface and description exactly how the author's analytical framework stands out from the crowd, but the topic interests me more than enough to give it a whirl to find out.

• Strategies of North and South: A Comparative Analysis of the Union and Confederate Campaigns by Gerald L. Earley (McFarland, 2021). From the description: "Since the Antebellum days there has been a tendency to view the South as martially superior to the North. In the years leading up to the Civil War, Southern elites viewed Confederate soldiers as gallant cavaliers, their Northern enemies as mere brutish inductees. "An effort to give an unbiased appraisal," Strategies of North and South: A Comparative Analysis of the Union and Confederate Campaigns "investigates the validity of this perception, examining the reasoning behind the belief in Southern military supremacy, why the South expected to win, and offering an cultural comparison of the antebellum North and South. The author evaluates command leadership, battle efficiency, variables affecting the outcomes of battles and campaigns, and which side faced the more difficult path to victory and demonstrated superior strategy." The book begins with a pair of chapters that examine antebellum and secession period perceptions of the martial prowess and traditions of each section. This is followed by a year by year analysis of campaigns and battles "with a view of delivering a non-biased assessment of performance as well as outcomes" that "takes into account the challenges and circumstances encountered during the course of the war" (pg. 2). The author readily admits that his approach (campaigns are selected "based on their relevance to the book's objective") is "inherently subjective." It's still unclear from reading the preface and description exactly how the author's analytical framework stands out from the crowd, but the topic interests me more than enough to give it a whirl to find out.

Friday, July 16, 2021

Booknotes: The Most Hated Man in Kentucky

New Arrival:

• The Most Hated Man in Kentucky: The Lost Cause and the Legacy of Union General Stephen Burbridge by Brad Asher (UP of Ky, 2021). From the description: "For the last third of the nineteenth century, Union General Stephen Gano Burbridge enjoyed the unenviable distinction of being the most hated man in Kentucky. From mid-1864, just months into his reign as the military commander of the state, until his death in December 1894, the mere mention of his name triggered a firestorm of curses from editorialists and politicians." Burbridge was not the only Union general to be accused during and after the war of installing an arbitrary military rule over the home front that encompassed widespread abuse of the civilian population (including the loyal Kentucky majority under his charge). Readers might recall the recent publication of General E.A. Paine in Western Kentucky: Assessing the "Reign of Terror" of the Summer of 1864 (2018). In similar vein, Brad Asher's The Most Hated Man in Kentucky: The Lost Cause and the Legacy of Union General Stephen Burbridge reassesses the contentious historical reputation of its subject. More from the description: "In this revealing biography, Brad Asher explores how Burbridge earned his infamous reputation and adds an important new layer to the ongoing reexamination of Kentucky during and after the Civil War. Asher illuminates how Burbridge―as both a Kentuckian and the local architect of the destruction of slavery―became the scapegoat for white Kentuckians, including many in the Unionist political elite, who were unshakably opposed to emancipation." In addition to "recalibrating history's understanding of Burbridge," The Most Hated Man in Kentucky "adds administrative and military context to the state's reaction to emancipation and sheds new light on its postwar pro-Confederacy shift."

• The Most Hated Man in Kentucky: The Lost Cause and the Legacy of Union General Stephen Burbridge by Brad Asher (UP of Ky, 2021). From the description: "For the last third of the nineteenth century, Union General Stephen Gano Burbridge enjoyed the unenviable distinction of being the most hated man in Kentucky. From mid-1864, just months into his reign as the military commander of the state, until his death in December 1894, the mere mention of his name triggered a firestorm of curses from editorialists and politicians." Burbridge was not the only Union general to be accused during and after the war of installing an arbitrary military rule over the home front that encompassed widespread abuse of the civilian population (including the loyal Kentucky majority under his charge). Readers might recall the recent publication of General E.A. Paine in Western Kentucky: Assessing the "Reign of Terror" of the Summer of 1864 (2018). In similar vein, Brad Asher's The Most Hated Man in Kentucky: The Lost Cause and the Legacy of Union General Stephen Burbridge reassesses the contentious historical reputation of its subject. More from the description: "In this revealing biography, Brad Asher explores how Burbridge earned his infamous reputation and adds an important new layer to the ongoing reexamination of Kentucky during and after the Civil War. Asher illuminates how Burbridge―as both a Kentuckian and the local architect of the destruction of slavery―became the scapegoat for white Kentuckians, including many in the Unionist political elite, who were unshakably opposed to emancipation." In addition to "recalibrating history's understanding of Burbridge," The Most Hated Man in Kentucky "adds administrative and military context to the state's reaction to emancipation and sheds new light on its postwar pro-Confederacy shift."

Wednesday, July 14, 2021

Review - "Six Days of Awful Fighting: Cavalry Operations on the Road to Cold Harbor" by Eric Wittenberg

[Six Days of Awful Fighting: Cavalry Operations on the Road to Cold Harbor by Eric J. Wittenberg (Fox Run Publishing, 2021). Hardcover, 25 maps, photos, footnotes, OB appendix series, bibliography, index. Pages main/total:vi,270/331. ISBN:978-1-945602-16-0. $36.95]

After nearly a month of continuous fighting in Virginia that resulted in appalling casualties on both sides, the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia and Union Army of the Potomac found themselves by late May 1864 in yet another close embrace, this time along the North Anna River where another major battle was only narrowly avoided. Up to that time, the Cavalry Corps of the Army of the Potomac under its new commanding general Philip Sheridan had performed unevenly, with a rather inauspicious Wilderness debut and a long raid toward Richmond that was successful only in mortally wounding JEB Stuart at Yellow Tavern on May 11. After Sheridan resumed his place alongside the rest of the army, his job was to clear the way for yet another complicated passage of the Army of the Potomac around Lee's right. This new turning movement would involve a jump across the Pamunkey River, a potentially risky endeavor that would embroil the mounted forces of both sides in a week-long series of skirmishes and battles. That drawn-out episode of heated action fought during the 1864 Overland Campaign is the subject of prolific author and eastern theater cavalry expert Eric Wittenberg's latest study Six Days of Awful Fighting: Cavalry Operations on the Road to Cold Harbor. In the book Wittenberg discusses vividly and in great detail the series of cavalry actions fought amid the late-May repositioning of the main armies in Virginia, first to Totopotomoy Creek then to new opposing lines around Cold Harbor. The first action, a Union victory at Hanovertown on May 27, effectively cleared the way for the Army of the Potomac's Pamunkey River crossing. Seeking to block further progress of the enemy until his own infantry could get into an advantageous position, Lee sent his cavalry toward the front, and a large battle with Sheridan's men developed at Haw's Shop on May 28. Fought mostly dismounted and in rough terrain, it is the action recounted at greatest length in the book. At Haw's Shop, Wade Hampton (the heir apparent to Stuart) was soundly defeated but nevertheless succeeded in keeping Sheridan's otherwise victorious forces from locating the main body of Lee's army. As addressed in the book, Haw's Shop revealed several themes that developed over the week. The first revolves around Hampton's inexperience in meeting the demands of corps-level leadership. He would prove himself a superb addition to the ANV high command later on, but his decision-making during the battle directly led to unnecessary losses and the near rout of his forces. On the other side, Sheridan, though the victor, is criticized for unimaginative tactics and for not following up on his triumph. A more general Union misuse of cavalry during the Overland Campaign is another major theme explored in the book. According to Wittenberg's analysis, the eastern Union army's high command triumvirate of Grant, Meade, and Sheridan were all guilty of that offense, though for different reasons. Meade wanted to use his mounted forces to closely guard his army's rear, its trains, and its flanks, while Grant and Sheridan favored concentrating the corps for large-scale movements behind enemy lines. All neglected what Wittenberg persuasively maintains to have been of primary importance, the gathering of intelligence as to the exact whereabouts of the enemy and the screening of the main army's advance. Because of this signal failure, the author maintains that Union forces were very fortunate that disaster did not ensue at some point. Wittenberg is also critical of Confederate handling of their own mounted forces, specifically Lee's organizational decision to delay the appointment of a successor to Stuart. In the immediate wake of Stuart's demise, Lee relied on all three division commanders to cooperate with each other and report directly to him for instructions. Leaving the cavalry corps without the strong head needed should any dangerously fluid situation arise, this command structure could have had profoundly negative results, but the author credits Hampton and the two Lees (Fitzhugh and Rooney) for handling the awkward situation as well as could be expected. On the 29th, instead of using their cavalry to quickly probe ahead to locate Lee's army, Grant and Meade advanced three infantry divisions. That ponderous means of intelligence gathering is justly criticized by the author. The cavalry did remain active, though. With both sides recognizing the need to address their open eastern flank and seeing the value of holding the crossroads at Old Cold Harbor, a sharp fight developed on May 30 at Matadequin Creek that pitted Alfred Torbert's Union division against Matthew Butler's large but inexperienced brigade of South Carolinians. It was yet another Union victory, but, according to the author, it also proved to skeptical ANV veterans the fighting abilities of Butler and his untried men. Also covered in the book is Union cavalry division commander James Wilson's raid against the South Anna railroad bridges, an operation that started out well with Wilson beating Rooney Lee at Hanover Court House on May 31. To the east on that same day, Torbert drove two brigades of Confederate cavalry and Thomas Clingman's brigade of Robert Hoke's infantry division out of Cold Harbor and repurposed the enemy earthworks there for his own use. On the next day, Confederate reinforcements converged on Ashland to drive Wilson off and nearly destroy one of his brigades, but not before the twin South Anna bridges were successfully burned. With the bridges rapidly repaired, however, Wilson's operation did not have any long-term effect. Finally, the book ends with the return of Confederate forces to Cold Harbor, where a disorganized infantry attack was easily repulsed by the entrenched Union cavalry. This action set up the terrible events that would unfold over the next few days. One might have expected that by mid-1864 the cavalry corps of the Army of the Potomac would have been led by grizzled veteran commanders of long-standing mounted service, but that was not the case. Wittenberg interestingly points out the irony that Union success over the week-long period covered in his book was primarily accomplished by generals of little field experience leading cavalry (Wilson) or those with infantry backgrounds (Sheridan and Torbert). Only division commander David M. Gregg was a cavalryman through and through, and he was oddly marginalized by Sheridan. Further, Wittenberg astutely observes that this command arrangement had few negative effects overall, as the cavalry mostly fought dismounted in infantry-style engagements supported by their prodigious firepower advantages in breechloading arms and elite horse artillery. The Union army's Cavalry Corps also possessed an excellent assemblage of veteran brigade commanders. On the other side, the Confederate cavalry had to suffer a bit through Hampton's acclimation to his expanded responsibilities while also laboring under systemic disadvantages stemming from inferior cavalry arms technology and the campaign's sustained operations exposing the lack of a central remount system. Nevertheless, as the author explains, the series of Union victories achieved over the six days covered in the book did not augur a complete mastery over the foe, as Hampton dealt Sheridan a sharp defeat only weeks later at Trevilian Station. Tantalizingly, at least one Union participant quoted in the text claimed that the Confederate cavalry did not fight as hard as they did before Yellow Tavern. This perception from an enemy observer that widespread demoralization existed among the Confederate cavalry corps's rank and file after Stuart's death is not directly addressed by the author at any length, but judging from the content and tenor of the book's narrative as a whole it would not appear that Wittenberg holds much stock in that view. There is nothing to complain about when it comes to the technical side of the book as well as its overall presentation. Clear and insightful operational and tactical narrative, deep research, and abundant maps are characteristics of all of Wittenberg's military history studies, and we certainly encounter those qualities yet again here with Six Days of Awful Fighting's excellent battlefield accounts, primary source-filled bibliography, and 25 maps. Orders of battle for each major engagement [Hanovertown Ferry (May 27), Haw's Shop (May 28), Old Church/Matadequin Creek (May 30), Hanover Court House (May 31), Cold Harbor (May 31), Ashland (June 1), and Cold Harbor again (June 1)] are also helpfully included in the appendix section. In unprecedented fashion, the book reveals a number of cavalry (as well as army high command) leadership flaws and strengths that emerged on both sides during the 1864 Overland Campaign while also presenting mounted operations fought during a major phase of that campaign in fresh ways that greatly promote higher understanding of decisions and events leading up to the early June climax of the Battle of Cold Harbor. Highly recommended.

After nearly a month of continuous fighting in Virginia that resulted in appalling casualties on both sides, the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia and Union Army of the Potomac found themselves by late May 1864 in yet another close embrace, this time along the North Anna River where another major battle was only narrowly avoided. Up to that time, the Cavalry Corps of the Army of the Potomac under its new commanding general Philip Sheridan had performed unevenly, with a rather inauspicious Wilderness debut and a long raid toward Richmond that was successful only in mortally wounding JEB Stuart at Yellow Tavern on May 11. After Sheridan resumed his place alongside the rest of the army, his job was to clear the way for yet another complicated passage of the Army of the Potomac around Lee's right. This new turning movement would involve a jump across the Pamunkey River, a potentially risky endeavor that would embroil the mounted forces of both sides in a week-long series of skirmishes and battles. That drawn-out episode of heated action fought during the 1864 Overland Campaign is the subject of prolific author and eastern theater cavalry expert Eric Wittenberg's latest study Six Days of Awful Fighting: Cavalry Operations on the Road to Cold Harbor. In the book Wittenberg discusses vividly and in great detail the series of cavalry actions fought amid the late-May repositioning of the main armies in Virginia, first to Totopotomoy Creek then to new opposing lines around Cold Harbor. The first action, a Union victory at Hanovertown on May 27, effectively cleared the way for the Army of the Potomac's Pamunkey River crossing. Seeking to block further progress of the enemy until his own infantry could get into an advantageous position, Lee sent his cavalry toward the front, and a large battle with Sheridan's men developed at Haw's Shop on May 28. Fought mostly dismounted and in rough terrain, it is the action recounted at greatest length in the book. At Haw's Shop, Wade Hampton (the heir apparent to Stuart) was soundly defeated but nevertheless succeeded in keeping Sheridan's otherwise victorious forces from locating the main body of Lee's army. As addressed in the book, Haw's Shop revealed several themes that developed over the week. The first revolves around Hampton's inexperience in meeting the demands of corps-level leadership. He would prove himself a superb addition to the ANV high command later on, but his decision-making during the battle directly led to unnecessary losses and the near rout of his forces. On the other side, Sheridan, though the victor, is criticized for unimaginative tactics and for not following up on his triumph. A more general Union misuse of cavalry during the Overland Campaign is another major theme explored in the book. According to Wittenberg's analysis, the eastern Union army's high command triumvirate of Grant, Meade, and Sheridan were all guilty of that offense, though for different reasons. Meade wanted to use his mounted forces to closely guard his army's rear, its trains, and its flanks, while Grant and Sheridan favored concentrating the corps for large-scale movements behind enemy lines. All neglected what Wittenberg persuasively maintains to have been of primary importance, the gathering of intelligence as to the exact whereabouts of the enemy and the screening of the main army's advance. Because of this signal failure, the author maintains that Union forces were very fortunate that disaster did not ensue at some point. Wittenberg is also critical of Confederate handling of their own mounted forces, specifically Lee's organizational decision to delay the appointment of a successor to Stuart. In the immediate wake of Stuart's demise, Lee relied on all three division commanders to cooperate with each other and report directly to him for instructions. Leaving the cavalry corps without the strong head needed should any dangerously fluid situation arise, this command structure could have had profoundly negative results, but the author credits Hampton and the two Lees (Fitzhugh and Rooney) for handling the awkward situation as well as could be expected. On the 29th, instead of using their cavalry to quickly probe ahead to locate Lee's army, Grant and Meade advanced three infantry divisions. That ponderous means of intelligence gathering is justly criticized by the author. The cavalry did remain active, though. With both sides recognizing the need to address their open eastern flank and seeing the value of holding the crossroads at Old Cold Harbor, a sharp fight developed on May 30 at Matadequin Creek that pitted Alfred Torbert's Union division against Matthew Butler's large but inexperienced brigade of South Carolinians. It was yet another Union victory, but, according to the author, it also proved to skeptical ANV veterans the fighting abilities of Butler and his untried men. Also covered in the book is Union cavalry division commander James Wilson's raid against the South Anna railroad bridges, an operation that started out well with Wilson beating Rooney Lee at Hanover Court House on May 31. To the east on that same day, Torbert drove two brigades of Confederate cavalry and Thomas Clingman's brigade of Robert Hoke's infantry division out of Cold Harbor and repurposed the enemy earthworks there for his own use. On the next day, Confederate reinforcements converged on Ashland to drive Wilson off and nearly destroy one of his brigades, but not before the twin South Anna bridges were successfully burned. With the bridges rapidly repaired, however, Wilson's operation did not have any long-term effect. Finally, the book ends with the return of Confederate forces to Cold Harbor, where a disorganized infantry attack was easily repulsed by the entrenched Union cavalry. This action set up the terrible events that would unfold over the next few days. One might have expected that by mid-1864 the cavalry corps of the Army of the Potomac would have been led by grizzled veteran commanders of long-standing mounted service, but that was not the case. Wittenberg interestingly points out the irony that Union success over the week-long period covered in his book was primarily accomplished by generals of little field experience leading cavalry (Wilson) or those with infantry backgrounds (Sheridan and Torbert). Only division commander David M. Gregg was a cavalryman through and through, and he was oddly marginalized by Sheridan. Further, Wittenberg astutely observes that this command arrangement had few negative effects overall, as the cavalry mostly fought dismounted in infantry-style engagements supported by their prodigious firepower advantages in breechloading arms and elite horse artillery. The Union army's Cavalry Corps also possessed an excellent assemblage of veteran brigade commanders. On the other side, the Confederate cavalry had to suffer a bit through Hampton's acclimation to his expanded responsibilities while also laboring under systemic disadvantages stemming from inferior cavalry arms technology and the campaign's sustained operations exposing the lack of a central remount system. Nevertheless, as the author explains, the series of Union victories achieved over the six days covered in the book did not augur a complete mastery over the foe, as Hampton dealt Sheridan a sharp defeat only weeks later at Trevilian Station. Tantalizingly, at least one Union participant quoted in the text claimed that the Confederate cavalry did not fight as hard as they did before Yellow Tavern. This perception from an enemy observer that widespread demoralization existed among the Confederate cavalry corps's rank and file after Stuart's death is not directly addressed by the author at any length, but judging from the content and tenor of the book's narrative as a whole it would not appear that Wittenberg holds much stock in that view. There is nothing to complain about when it comes to the technical side of the book as well as its overall presentation. Clear and insightful operational and tactical narrative, deep research, and abundant maps are characteristics of all of Wittenberg's military history studies, and we certainly encounter those qualities yet again here with Six Days of Awful Fighting's excellent battlefield accounts, primary source-filled bibliography, and 25 maps. Orders of battle for each major engagement [Hanovertown Ferry (May 27), Haw's Shop (May 28), Old Church/Matadequin Creek (May 30), Hanover Court House (May 31), Cold Harbor (May 31), Ashland (June 1), and Cold Harbor again (June 1)] are also helpfully included in the appendix section. In unprecedented fashion, the book reveals a number of cavalry (as well as army high command) leadership flaws and strengths that emerged on both sides during the 1864 Overland Campaign while also presenting mounted operations fought during a major phase of that campaign in fresh ways that greatly promote higher understanding of decisions and events leading up to the early June climax of the Battle of Cold Harbor. Highly recommended.

Monday, July 12, 2021

Booknotes: The Siege of Vicksburg

New Arrival:

• The Siege of Vicksburg: Climax of the Campaign to Open the Mississippi River, May 23-July 4, 1863 by Timothy B. Smith (UP of Kansas, 2021). After decades of neglect, book-length studies of various stages of the long 1862-63 Vicksburg Campaign are finally arriving to fill in the gaps and augment classic works such as the Bearss trilogy. Soon after the release of two books that covered in great depth the May 19 and May 22 assaults (one each from the prolific pair of military historians Timothy Smith and Earl Hess) is Smith's The Siege of Vicksburg: Climax of the Campaign to Open the Mississippi River, May 23-July 4, 1863. A direct follow up to his previous book, Smith's new volume represents the first comprehensive, standalone narrative history of the siege, and a big one it is at nearly 550 pages of main text. Siege tactics and operations along with other aspects of the static phase of campaign have been discussed in other books, but Smith brings it all together in a single, cohesive account supported by 19 original maps. The book "offers a new perspective and thus a fuller understanding of the larger Vicksburg Campaign. Smith takes full advantage of all the resources, both Union and Confederate—from official reports to soldiers’ diaries and letters to newspaper accounts—to offer in vivid detail a compelling narrative of the operations. The siege was unlike anything Grant’s Army of the Tennessee had attempted to this point and Smith helps the reader understand the complexity of the strategy and tactics, the brilliance of the engineers’ work, the grueling nature of the day-by-day participation, and the effect on all involved, from townspeople to the soldiers manning the fortifications." More from the description: Smith's "detailed command-level analysis extends from army to corps, brigades, and regiments and offers fresh insights on where each side held an advantage. One key advantage was that the Federals had vast confidence in their commander while the Confederates showed no such assurance, whether it was Pemberton inside Vicksburg or Johnston outside." The ground-level perspectives of both sides are also detailed, as Smith "offers an equally appealing and richly drawn look at the combat experiences of the soldiers in the trenches." Smith "also tackles the many controversies surrounding the siege, including detailed accounts and analyses of Johnston’s efforts to lift the siege, and answers the questions of why Vicksburg fell and what were the ultimate consequences of Grant’s victory." Among those topics, Smith's coverage of the activities of Joe Johnston's Army of Relief as well as his overall interpretation of the general's conduct during the campaign will be of particular interest to me.

• The Siege of Vicksburg: Climax of the Campaign to Open the Mississippi River, May 23-July 4, 1863 by Timothy B. Smith (UP of Kansas, 2021). After decades of neglect, book-length studies of various stages of the long 1862-63 Vicksburg Campaign are finally arriving to fill in the gaps and augment classic works such as the Bearss trilogy. Soon after the release of two books that covered in great depth the May 19 and May 22 assaults (one each from the prolific pair of military historians Timothy Smith and Earl Hess) is Smith's The Siege of Vicksburg: Climax of the Campaign to Open the Mississippi River, May 23-July 4, 1863. A direct follow up to his previous book, Smith's new volume represents the first comprehensive, standalone narrative history of the siege, and a big one it is at nearly 550 pages of main text. Siege tactics and operations along with other aspects of the static phase of campaign have been discussed in other books, but Smith brings it all together in a single, cohesive account supported by 19 original maps. The book "offers a new perspective and thus a fuller understanding of the larger Vicksburg Campaign. Smith takes full advantage of all the resources, both Union and Confederate—from official reports to soldiers’ diaries and letters to newspaper accounts—to offer in vivid detail a compelling narrative of the operations. The siege was unlike anything Grant’s Army of the Tennessee had attempted to this point and Smith helps the reader understand the complexity of the strategy and tactics, the brilliance of the engineers’ work, the grueling nature of the day-by-day participation, and the effect on all involved, from townspeople to the soldiers manning the fortifications." More from the description: Smith's "detailed command-level analysis extends from army to corps, brigades, and regiments and offers fresh insights on where each side held an advantage. One key advantage was that the Federals had vast confidence in their commander while the Confederates showed no such assurance, whether it was Pemberton inside Vicksburg or Johnston outside." The ground-level perspectives of both sides are also detailed, as Smith "offers an equally appealing and richly drawn look at the combat experiences of the soldiers in the trenches." Smith "also tackles the many controversies surrounding the siege, including detailed accounts and analyses of Johnston’s efforts to lift the siege, and answers the questions of why Vicksburg fell and what were the ultimate consequences of Grant’s victory." Among those topics, Smith's coverage of the activities of Joe Johnston's Army of Relief as well as his overall interpretation of the general's conduct during the campaign will be of particular interest to me.

Thursday, July 8, 2021

Booknotes: Military Prisons of the Civil War

New Arrival:

• Military Prisons of the Civil War: A Comparative Study by David L. Keller (Westholme, 2021). That the American Civil War military prisoner population was the largest in history up to its time is not something that I had previously considered. It might be true, though one can imagine that the Napoleonic Wars, the many participants of which also detained surrendered combatants in large numbers for extended periods of time, could have exceeded even the ACW's massive figure as that earlier continental conflict was fought over a much longer period of time and witnessed a great many mass capitulations. Anyway, getting back to the matter at hand, that is the claim made in David Keller's new book Military Prisons of the Civil War: A Comparative Study, which offers "a fresh analysis of the first large-scale imprisonment of soldiers in wartime and its failures." From the description: "Over the course of the American Civil War, more than four hundred thousand prisoners were taken by the North and South combined—the largest number in any conflict up to that time, and nearly fifty-eight thousand of these men died while incarcerated or soon after being released. Neither side expected to take so many prisoners in the wake of battles and neither had any experience on how to deal with such large numbers." Of course, dealing with such a burden had a learning curve that already overtaxed Union and Confederate governments and militaries had to very swiftly address, and accusations of abuse and incompetence abounded on both sides. "Prison camps were quickly established, and as the war progressed, reports of sickness, starvation, mistreatment by guards, and other horrors circulated in the press. After the war, recriminations were leveled on both sides, and much of the immediate ill-will between the North and South dealt with prisoners and their treatment." Using "official records, newspaper reports, first-person accounts from prisoners, and other primary source material," Keller seeks to "understand why imprisonment during the Civil War failed on both sides. His research identifies five factors shared among both Union and Confederate prisons that led to so many deaths, including the lack of a strategic plan on either side for handling prisoners, inadequate plans for holding prisoners for long periods of time, and poor selection and training of camp command and guards."

• Military Prisons of the Civil War: A Comparative Study by David L. Keller (Westholme, 2021). That the American Civil War military prisoner population was the largest in history up to its time is not something that I had previously considered. It might be true, though one can imagine that the Napoleonic Wars, the many participants of which also detained surrendered combatants in large numbers for extended periods of time, could have exceeded even the ACW's massive figure as that earlier continental conflict was fought over a much longer period of time and witnessed a great many mass capitulations. Anyway, getting back to the matter at hand, that is the claim made in David Keller's new book Military Prisons of the Civil War: A Comparative Study, which offers "a fresh analysis of the first large-scale imprisonment of soldiers in wartime and its failures." From the description: "Over the course of the American Civil War, more than four hundred thousand prisoners were taken by the North and South combined—the largest number in any conflict up to that time, and nearly fifty-eight thousand of these men died while incarcerated or soon after being released. Neither side expected to take so many prisoners in the wake of battles and neither had any experience on how to deal with such large numbers." Of course, dealing with such a burden had a learning curve that already overtaxed Union and Confederate governments and militaries had to very swiftly address, and accusations of abuse and incompetence abounded on both sides. "Prison camps were quickly established, and as the war progressed, reports of sickness, starvation, mistreatment by guards, and other horrors circulated in the press. After the war, recriminations were leveled on both sides, and much of the immediate ill-will between the North and South dealt with prisoners and their treatment." Using "official records, newspaper reports, first-person accounts from prisoners, and other primary source material," Keller seeks to "understand why imprisonment during the Civil War failed on both sides. His research identifies five factors shared among both Union and Confederate prisons that led to so many deaths, including the lack of a strategic plan on either side for handling prisoners, inadequate plans for holding prisoners for long periods of time, and poor selection and training of camp command and guards."

Tuesday, July 6, 2021

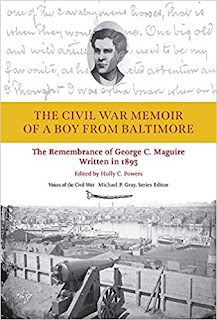

Review - "The Civil War Memoir of a Boy from Baltimore: The Remembrance of George C. Maguire, Written in 1893" by Holly Powers, ed.

[The Civil War Memoir of a Boy from Baltimore: The Remembrance of George C. Maguire, Written in 1893 edited by Holly I. Powers (University of Tennessee Press, 2021). Hardcover, photos, drawings, notes, bibliography, index. Pages:xxvi,133. ISBN:978-1-62190-335-2. $45]

A great multitude of underage soldiers served in the fighting ranks of Civil War armies of both sides (some estimates maintain that one-fifth of all Union soldiers were under the prescribed age of eighteen at enlistment). Impressed by the promise of grand adventure or any of a number of additional motivating factors, other boys too young to shoulder a rifle accompanied regiments as drummer boys or unit "mascots" looked after by the older officers and men. Mascots that demonstrated maturity beyond their years could even be assigned a certain degree of real responsibility in either official or unofficial roles. This was the case with Baltimore's George C. Maguire. Though his own deeds attained far less fame than those of some other Union child soldiers such as John Clem (a.k.a. "Johnny Shiloh"), Orion P. Howe, or Manny Root, young Maguire nevertheless contributed to the war in ways no less worthy of recognition. With the publication of The Civil War Memoir of a Boy from Baltimore: The Remembrance of George C. Maguire, Written in 1893, the newest volume in University of Tennessee Press's Voices of the Civil War series, a great many Civil War readers can now be fully exposed to Maguire's wartime activities through the efforts of editor Holly Powers.

In his memoir Maguire claimed to be "around 12" years of age when Fort Sumter was fired upon, but Powers's examination of census records indicates that he would have been closer to 14. The memoir's earliest wartime remembrances include observations of the violent 1861 rioting in Maguire's native Baltimore, made perhaps most interesting to today's readers for the writer's unconventional determination that the infamous assaults on passing Union soldiers were primarily motivated by false assumptions about the war and over two-thirds of the perpetrators would eventually see the error of their ways and enthusiastically join the Union Army. How Maguire arrived at such a number is unknown, but perhaps, as he came from a solidly pro-Union family, he wanted to present his fellow Baltimoreans in a more favorable (i.e. more loyal) light.

Maguire was allowed/invited to join his brother-in-law Lt. Salome Marsh (whom he lived with before the war) and two brothers in the Fifth Maryland, a volunteer infantry regiment that received its training at nearby Camp LaFayette and first field assignment at Fort Monroe in Virginia. The regiment did not participate in any of the Peninsula and Seven Days battles, and Maguire relates mostly boyish adventures on the Hampton Roads stretch of the Virginia Peninsula. However, during the 1862 Maryland Campaign Maguire would in more earnest begin his transformation from army tourist to active participant. He came under fire at Antietam (the Fifth was involved in the Second Corps attack on the Bloody Lane) and assisted the regimental surgeon in caring for the wounded. Traumatized by the experience, he returned home to Baltimore and reentered school. However, Maguire quickly became bored with the routine of home and school life, and rejoined the regiment at the end of 1862.

At the time of Maguire's return the Fifth was part of the Harpers Ferry garrison, and Lt. Marsh was provost marshal. Marsh employed the educated Maguire as an office clerk with document-issuing powers, and Maguire's memoir offers an eventful picture of Potomac River smuggling operations and the inner workings of the pass system for civilians traveling both directions through Harpers Ferry. This job would be his final one at the front. In June 1863, Maguire left the regiment altogether and returned home. There would be one final attempt to rejoin the war, though. Tempted by the considerable allure of the high fees being paid to late-war substitutes, Maguire tried to engage a broker in the city but was rejected.

In 1865, Maguire obtained employment at Maryland's new Thomas Hicks United States General Hospital. Impressed by his wartime experience (slim as it was) and his education, staff assigned Maguire a posting as Ward Master, and he was even given Medical Cadet status by the supervising physician as a way to allow Maguire to assume expanded duties related to direct patient care. Though this part of the memoir is relatively brief, it contains a number of empathetic patient stories as well as useful information regarding the layout and operation of the hospital. A number of Maguire's sketches are reproduced in the book, and the ones related to the hospital are the most revealing.

The memoir itself is a quick read, running sixty pages in the book. As part of her editorial duties, Powers contributes a scholarly introduction, a chapter-length conclusion, and extensive endnotes to the volume. Quite expansive discussions of persons, objects, places, and events are contained in her notes, and the editor frequently found in her research documented confirmation of Maguire's experiences and observations. Over the past few decades, the Civil War scholarship has examined in far more depth than ever before the many ways in which children engaged with the Civil War and were affected by it (most readers will be at least familiar with James Marten's work, but there are many others), and The Civil War Memoir of a Boy from Baltimore is another strong resource and contribution to that subfield.

Sunday, July 4, 2021

Happy 4th of July!

I hope everyone has an enjoyable Fourth, and, since everything comes down to books on this site, what better way is there to celebrate our nation's independence and also recognize one of the Civil War's pivotal events that occurred on that very month and day in 1863 than by cracking open Timothy Smith's The Siege of Vicksburg: Climax of the Campaign to Open the Mississippi River, May 23-July 4, 1863, which has just received a timely release by publisher University Press of Kansas. I have not received my copy of this colossal new history of the Vicksburg siege and surrender yet but am looking forward to reading it this month.

Friday, July 2, 2021

Booknotes: From Arlington to Appomattox

New Arrival:

• From Arlington to Appomattox: Robert E. Lee’s Civil War, Day by Day, 1861-1865 by Charles R. Knight (Savas Beatie, 2021). Though not part of their regular publishing lineup, Savas Beatie does occasionally produce reference books alongside their more typical output of campaign/battle histories, military biographies, and more. Their newest title in that category is From Arlington to Appomattox: Robert E. Lee’s Civil War, Day by Day, 1861-1865. In it "author Charles Knight does for Lee and students of the war what E.B. Long’s Civil War Day by Day did for our ability to understand the conflict as a whole." From the description: "Lost in all of the military histories of the war, and even in most of the Lee biographies, is what the general was doing when he was out of history’s “public” eye. We know Lee rode out to meet the survivors of Pickett’s Charge and accept blame for the defeat, that he tried to lead the Texas Brigade in a counterattack to save the day at the Wilderness, and took a tearful ride from Wilmer McLean’s house at Appomattox. But what of the other days? Where was Lee and what was he doing when the spotlight of history failed to illuminate him?" One can imagine that a resource such as this one will save authors and researchers studying the Army of Northern Virginia, eastern theater campaigns, and Lee himself a lot of time in pinning down activities, dates, and places. On a more general level, an information compilation like this one should also contribute to our knowledge and appreciation of the range of daily burdens and responsibilities assumed by anyone tasked with leading a major Civil War army. "Readers will come away with a fresh sense of his struggles, both personal and professional, and discover many things about Lee for the first time using his own correspondence and papers from his family, his staff, his lieutenants, and the men of his army." Source information and extensive editorial text are conveniently placed in the footnotes, and the author also took the effort to create an index of names, events, places, units, and more with expansive subheadings to go along with the page numbers.

• From Arlington to Appomattox: Robert E. Lee’s Civil War, Day by Day, 1861-1865 by Charles R. Knight (Savas Beatie, 2021). Though not part of their regular publishing lineup, Savas Beatie does occasionally produce reference books alongside their more typical output of campaign/battle histories, military biographies, and more. Their newest title in that category is From Arlington to Appomattox: Robert E. Lee’s Civil War, Day by Day, 1861-1865. In it "author Charles Knight does for Lee and students of the war what E.B. Long’s Civil War Day by Day did for our ability to understand the conflict as a whole." From the description: "Lost in all of the military histories of the war, and even in most of the Lee biographies, is what the general was doing when he was out of history’s “public” eye. We know Lee rode out to meet the survivors of Pickett’s Charge and accept blame for the defeat, that he tried to lead the Texas Brigade in a counterattack to save the day at the Wilderness, and took a tearful ride from Wilmer McLean’s house at Appomattox. But what of the other days? Where was Lee and what was he doing when the spotlight of history failed to illuminate him?" One can imagine that a resource such as this one will save authors and researchers studying the Army of Northern Virginia, eastern theater campaigns, and Lee himself a lot of time in pinning down activities, dates, and places. On a more general level, an information compilation like this one should also contribute to our knowledge and appreciation of the range of daily burdens and responsibilities assumed by anyone tasked with leading a major Civil War army. "Readers will come away with a fresh sense of his struggles, both personal and professional, and discover many things about Lee for the first time using his own correspondence and papers from his family, his staff, his lieutenants, and the men of his army." Source information and extensive editorial text are conveniently placed in the footnotes, and the author also took the effort to create an index of names, events, places, units, and more with expansive subheadings to go along with the page numbers.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)