Wednesday, July 24, 2024

Review - "Union General Daniel Butterfield: A Civil War Biography" by James Pula

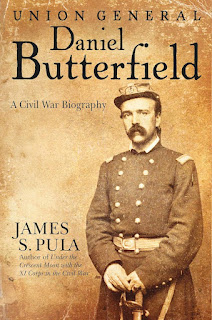

[Union General Daniel Butterfield: A Civil War Biography by James S. Pula (Savas Beatie, 2024). Hardcover, 13 maps, photos, illustrations, footnotes, bibliography, index. Pages main/total:xii,246/277. ISBN:978-1-61121-700-1. $32.95]

The military talents and accomplishments of Major General Daniel Adams Butterfield (1831-1901) were well recognized during his lifetime. However, that justly earned acclaim steadily diminished over the decades following his death. Today he is primarily remembered by Civil War students for his role in composing "Taps" and for his initiative in creating the army corps badges that, in simple but effective fashion, readily identified formation affiliation at a glance and contributed to unit pride. Most unfortunately, Butterfield is also often presented not as an individual officer with a sterling record of battlefield and administrative contributions but as a military politico connected at the hip to the ever controversial generals Joseph Hooker and Daniel Sickles.

Regardless of how he's been portrayed, a general of Butterfield's stature should have drawn the attention of at least one major biographer before now, but that has not been the case. Julia Lorrilard Butterfield, the general's second wife, did edit the 1904 volume A Biographical Memorial of General Daniel Butterfield, Including Many Addresses and Military Writings, but no full-length biography has ever been published before now. Finally rectifying that long-standing historiographical oversight is James Pula's Union General Daniel Butterfield, a relatively slim volume that nevertheless thoroughly explores Butterfield's prodigious civilian and military records of success. In addition, Pula's thoughtful study offers well-aimed and highly convincing answers to questions such as why Butterfield's rapid rise in the eastern theater's army high command peaked at Fredericksburg (where he led Fifth Corps in the field) and why his multifaceted career in uniform has been largely uncelebrated in the Civil War literature.

Although the source material necessary to provide a detailed portrait of Butterfield's earliest life apparently does not exist, Pula's biography is still a true cradle to grave treatment. Butterfield was born into a wealthy and well-connected family (his father was one of the founders of what would become American Express) and he received a strong education. Pre-Civil War coverage is most notable for Butterfield's successful integration into his family's business pursuits, where he made his own marks in management, innovation, and logistics, all of which informed the administrative genius that he demonstrated during his tenure as Army of the Potomac chief of staff under generals Hooker and George Gordon Meade. The same could be said for the management of his many different field commands, which were always maintained in proper fighting trim.

Pula details and judiciously assesses the progression of Butterfield's rise from regimental colonel to corps commander. A complete military amateur, Butterfield immersed himself in military self-learning, a process that he managed both thoroughly and at a breakneck pace. His 12th New York was widely lauded as being one of the volunteer army's best drilled and disciplined 90-Day regiments (even earning the highest praise from prickly old U.S. Army general in chief Winfield Scott). From there, Butterfield's brigade leadership on the Peninsula was instrumental to the Union victory at Hanover Court House, and his management of the extreme left flank at Gaines's Mill was solid as a rock before the line collapsed around him. For his personal bravery there he was later awarded the Medal of Honor. Butterfield assumed temporary command of a division at Second Manassas and stepped into that larger role with the same level of competence. Promoted to command of Fifth Corps over more senior professional officers (Meade being the most consequential complainant), his leadership conduct during the Battle of Fredericksburg and the skill he showed in fulfilling his assigned task of covering the withdrawal of the army upon its defeat both earned Butterfield additional performance plaudits.

Even after proving himself one of that dismal campaign's shining lights, Butterfield, to his complete dismay, was replaced at the head of Fifth Corps with Meade. Sidelined, Butterfield's fading star was rescued by Joseph Hooker when the newly appointed Army of the Potomac commander made Butterfield his chief of staff. It remains unclear exactly the degree to which Butterfield was the mastermind behind the grand suite of transformative winter 1862-63 army reforms so masterfully laid out in Albert Conner and Chris Mackowski's study Seizing Destiny: The Army of the Potomac's "Valley Forge" and the Civil War Winter that Saved the Union (2016), but it is unquestionable that it was Butterfield's task to carry them out. Unfortunately, defeat at Chancellorsville, and how it unfolded, overshadowed what was accomplished earlier by the duo.

When Hooker resigned just ahead of Gettysburg, Meade kept Butterfield on for the duration of the campaign but once the danger was over Butterfield left the army again, his flagging health forcing upon him another poorly timed sick leave. Meade took advantage of the indefinite absence and permanently replaced the ailing Butterfield with West Point career officer and engineer (and now major general) Andrew Humphreys. Once again, Butterfield's relationship with Hooker resurrected a stalled career arc, and he was brought in to serve as Hooker's chief of staff for the two-corps rescue operation sent west after the September 1863 Confederate victory at Chickamauga. During both campaigns, as Pula details, Butterfield was an untiring and exceptionally skilled handler of organization, logistics, intelligence processing, and march orders. When Hooker's men were consolidated into Twentieth Corps, Butterfield's chief of staff position was dropped and, though he was disappointed to not receive command of a corps, he was tasked with leading one of Hooker's divisions during the Atlanta Campaign. As Pula recounts, Butterfield distinguished himself at Resaca and other places before his delicate health failed him yet again. With that, Butterfield's fighting career was essentially over, though he did return to serve out the rest of the war in minor, less physically taxing administrative posts.

Off the battlefield, Butterfield found time early in the war to create an army manual, Camp and Outpost Duty for Infantry (1862), the practical value of which was so well received by professional army officers that it was recommended for army-wide use. In devising his own bugle calls to assist in managing his men amid the chaos and din of battle, Butterfield collaborated with bugler Oliver Norton, but he's better known for the composition of "Taps." Citing existing compositions such as the "Scott Tattoo," the originality of Butterfield's "Taps" has been disputed, but Pula is unconvinced by those arguments. In the book, he simply provides the sheet music of both for comparison while briefly noting his own view that "Taps" and the "Scott Tattoo" are "dramatically different in length and style," with only "modest similarities" in the last line (pg 60-61).

So, for all of those laurels and accomplishments earned in both combat leadership and military administration (none of which drew any corresponding degree of criticism from superiors, fellow officers, or political leaders), why was Butterfield's Civil War career progression characterized by a 'one step forward, two steps back' process that left him bitterly disappointed? Pula addresses that key question with powerful persuasiveness. At the top of the list of factors is the general's background and politics. Butterfield was not a West Pointer, and he was a Republican in an eastern army where West Point graduates of the more Democratic persuasion dominated top levels of command. Associated with those limitations were Butterfield's personal rivalry with Meade over who should command Fifth Corps and the former's injudicious decision to back the Sickles faction during the partisan post-Gettysburg Joint Committee investigation.

Perhaps equally significant was the degree to which Butterfield's career was tied to those of Hooker and Sickles. Outward appearances and perceptions mattered, and Butterfield came to be seen by critics as one of the defining figures in an army headquarters that became notorious in some circles as being "a combination of barroom and brothel" that no gentleman or lady could respectably enter. While most recent historians justly question the validity of that infamous assessment from the pen of Charles Francis Adams, Jr., it still has popular traction and was certainly damaging to Butterfield at the time. Unfortunately and unfairly, the result is that popular opinions of Butterfield lean more toward comparisons with politically tinged (or compromised) citizen-officers such as fellow major generals Stephen Hurlbut and Dan Sickles than they do the more truthfully fitting likes of highly capable non-professionals of similar rank such as John Logan, Grenville Dodge, and Jacob Cox.

From the collection of primary source observations that Pula cites, it is apparent that Butterfield's reputation within the army also suffered from being personally disliked by many brother officers. In reading the negative opinions presented in the book by those who came into contact with Butterfield, it seems he possessed the kind of 'smartest guy in the room' imperiousness that rubs people the wrong way regardless of the proven competence and intelligence behind its source.

Mentioned at regular intervals in the text, but perhaps not given enough emphasis by the author on its overall role in inhibiting Butterfield's career progression, was the precarious nature of the general's physical health throughout the war. Timing and simply being present and ready always figure prominently in military appointments, and plum corps-level assignments did not come up very often. Butterfield's sick leave after Gettysburg made it very easy for Meade to remove him and similar bodily health problems that arose during the first half of the 1864 campaign in North Georgia Campaign removed Butterfield from consideration during the many western high command shufflings that occurred subsequent to his health-induced absence. Assessing the degree to which overwork or a weak constitution figured most in his frequent absences (likely it was a combination of both) is difficult, but one might justly question whether Butterfield could stayed in the saddle consistently enough to reach his highest potential regardless of outside forces working against him.

The general also missed out on opportunities for self promotion. Even with those wartime health concerns referenced above, Butterfield still lived a long life, and his lack of interest in penning a Civil War memoir of the kind that propped up and cemented the martial reputations of so many other brother Civil War officers most certainly contributed to his relatively obscure status today. Taking all of the above into account, it becomes less puzzling as to the probable hows and whys behind Butterfield's Civil War field command ceiling and his rather disproportionately modest position in Civil War memory.

While Pula is quite obviously a great admirer of Butterfield, he also doesn't shrink from criticizing his subject when it's merited, nor does he fail to address the more damaging attacks on the general's character. In addition to lamenting Butterfield's siding with Sickles over the post-Gettysburg Sickles-Meade controversy, the author points to Butterfield's association with a major political and financial scandal after the war. During the partisan feeding frenzy attached to such things, there's a lot of guilt by association bandied about by various parties, and Pula concludes that the extent of Butterfield's involvement in gold market manipulation (he was a high-level U.S. Treasury appointee of the Grant administration) remains murky. What is beyond dispute was the hit to his reputation.

After the war, Butterfield greatly expanded upon his prewar business pursuits and amassed considerable wealth, which he generously applied to promotion of Union veteran affairs and war remembrance. Butterfield always returned to the short period of his life when he served his country with bravery and distinction, and it was fitting that his desire to be buried at West Point, for which special exception was needed, was granted.

James Pula's Union General Daniel Butterfield: A Civil War Biography comprehensively and responsibly restores the distinguished military reputation of its subject, a man who cheerfully shed the safety and comforts of the civilian world when his country called and proved to be both a gifted field general and one of the most able military administrators that the war produced. Upon finishing this volume, one is quite strongly tempted to go against the grain of popular understanding and rank Dan Butterfield among the war's top citizen-generals. Highly recommended.

4 comments:

***PLEASE READ BEFORE COMMENTING***: You must SIGN YOUR NAME ( First and Last) when submitting your comment. In order to maintain civil discourse and ease moderating duties, anonymous comments will be deleted. Comments containing outside promotions, self-promotion, and/or product links will also be removed. Thank you for your cooperation.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

An insightful and even handed review, Drew. Thank you.

ReplyDeleteHi Drew, Thank you so much for taking the time and trouble to do a deep-dive in what I, too, thought was a remarkable biography. Butterfield's contributions to the war were remarkable, and now, visible. Jim Pula did a wonderful job. -- Ted Savas, publisher

ReplyDeleteThank you for your very kind comments on my biography of Dan Butterfield. You presented an excellent summary of the main points of the book which gives the reader a very clear picture of what to expect between its covers. I hope it will lead other researchers and authors to reconsider the role of the protagonist in their own forthcoming works. Much appreciation for the care you took in crafting the review. – Jim Pula

ReplyDeleteI always liked his mention in 'The Killer Angels'/'Gettysburg': "You ever heard of Dan Butterfield? "The one that was with Hooker? Heard he was a pistol" and 'Taps' is mentioned of course plus his brigade bugle call as enacted by Tom Chamberlain: 'Dan, Dan, Dan, Butterfield, Butterfield'. Excellent review of yet another book to check out.

ReplyDelete